Bounds on the cross currency basis and why they have lessened

What is the cross currency basis?

The cross currency basis arises when pricing in the foreign exchange market diverges from what interest rate differentials would imply. This divergence creates a small additional return above the domestic interest rate.

This additional return can be earned by buying foreign currency (e.g. US dollars), investing at the foreign interest rate for three months (e.g. US Libor or T-bill), and selling the foreign currency proceeds (US dollars plus interest) for forward delivery in three months’ time.

The small additional return is termed the cross currency basis, as it represents the small gap between the domestic interest rate and what can be earned on a foreign interest rate after hedging costs are deducted.

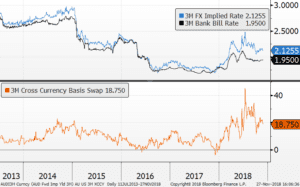

Figure 1: 3M Cross Currency Basis Swap

Why does the cross currency basis arise?

The cross currency basis exists because the balance of supply and demand in the interest rate markets differs from that in the foreign exchange market. This is due to the different participants in each market having different underlying objectives.

In the foreign exchange market, the presence of trade deficits and surpluses means that countries such as Japan tend to be net exporters of capital. That is, they generate a lot of foreign currency earnings because of their trade surplus position, and this foreign currency tends to get reinvested in other markets, often on a hedged basis.

The demand for hedging this creates can be larger than what can be accommodated by the bank balance sheets who make markets in foreign exchange. As a result, as banks approach their limits, forward foreign exchange rates adjust to make hedging more expensive. This creates a divergence in forward foreign exchange rates away from what would be implied by interest rate differentials alone, thus creating the cross currency basis.

Once a non-negligible cross currency basis is present, it can then be accessed as an additional source of return for investors who are able to undertake offshore investments while hedging the exchange rate risk. Investors are therefore rewarded for being prepared to go in the opposite direction to the bulk of hedging demand.

What sets the bounds on the cross currency basis?

Many influences from both the foreign exchange and interest rate markets influence how wide the cross currency basis can get, but two fundamental bounds relate to bank arbitrage and repo rates. Over the past year these bounds have fallen back considerably, which is why the cross currency basis has widened as much as it has.

1. Bank arbitrage

Bank arbitrage can help contain the cross currency basis, as when the difference between domestic interest rates and hedged foreign interest rates gets too large, a domestic bank can simply borrow at the domestic rate, and lend at the higher hedged foreign interest rate, and pocket the difference. This could occur by the bank issuing domestic bank bills, investing the proceeds in US dollars, and hedging the foreign exchange risk.

If this occurs in enough size, it will place upward pressure on domestic rates, as banks demand more funds domestically, and downward pressure on hedged foreign rates, as more investment and hedging in the foreign market takes place.

Historically however, the cross currency basis has persisted despite this constraint, in part because the size of bank arbitrage is fairly small compared to the much larger real economy flows that occur in the foreign exchange market.

In recent years, banks have also become considerably constrained in terms of balance sheet growth, which further limits the extent to which they can arbitrage the domestic rate and the hedged foreign rate.

2. Repo rates

The other factor which influences the bounds on the cross currency basis is the domestic repo rate. The repo rate is the interest rate on cash secured with general government bond collateral, in contrast to the bank bill rate which represents an unsecured exposure.

Some years back, repo rates used to trade in line with the cash rate, however more recently repo rates have often traded well above the cash rate, even without any expected change in the cash rate (i.e. flat OIS rates). The wider repo rates in part reflect the larger amount of physical bonds on issue, greater purchases of physical bonds using repo by foreign investors, and also regulatory pressure on banks to limit balance sheet growth.

The effect of higher repo rates has been to create an additional form of demand for cash from banks. This additional demand for cash has essentially competed with the foreign exchange market for cash from the banks.

Where a bank might previously have found it attractive to borrow using a bank bill at 1.90%, and invest the proceeds in the foreign exchange market and earn 2.10%, in some cases banks are now able to place cash on repo at 2% or even higher. This draws cash away from the foreign exchange market and into the repo market, and thus creates upward pressure on the cross currency basis as less balance sheet is available to be deployed in the foreign exchange market.

For this reason a further rise in the repo rate would likely place upward pressure on the cross currency basis, and vice versa as repo rates come down, the cross currency basis tends to narrow. This is essentially what we have observed over the past few months in Aussie domestic funding markets.