China risk goes beyond trade wars

The China economic slowdown story had actually been building behind the scenes long before markets decided to focus on trade hostilities with the US (refer to – Markets wake up to China risk).

Going back to October 2017’s Communist Party Congress, while President Xi Jinping was busy consolidating his personal power in a way no recent Chinese leader has, his less well known central bank governor at the time (Zhou Xiaochuan) was unusually outspoken about the risks that high debt levels posed to the Chinese economy and the need for closer scrutiny of leverage.

The very next month, the reality of the leadership’s renewed focus on controlling financial risks began setting in. Most notably, the government signalled a crackdown on popular wealth management products (WMP) sold by banks.

The very large (approx. USD4trn) and poorly regulated WMP industry offered high yielding debt investment products to retail investors that often include highly risky and illiquid underlying investments, which they are forced to rely on in order to generate the high rates of return promised to investors.

Meanwhile, the investments were marketed to investors as being ‘safe’ because they were wrapped into a neat WMP package with the perception of a guarantee from the bank selling them, even though there is no explicit guarantee.

Historically, standard practice had been for banks to bail out WMP structures where the underlying investments have failed, in order to protect their reputations and maintain this lucrative revenue source.

While these dynamics had been conveniently ignored in the past, regulatory scrutiny picked up because the sheer volume of these WMP products outstanding had become a potential systemic threat to the banking sector.

To pre-empt this risk, regulators announced a range of measures in late 2017 to restrict the marketing of these products. While positive for controlling excessive risk taking in the financial sector, the WMP sector was an important source of debt funding for many companies, which were increasingly left facing tighter credit conditions.

Even prior to these WMP measures, the leadership in Beijing had expressed concern about ‘grey rhinos’. This was not a reference to the Asian rhinoceros that once roamed across China, but rather to overly indebted companies.

The reference was made by the Communist Party newspaper, People’s Daily, in relation to financial stability risks posed by large Chinese corporates that have experienced rapid debt fuelled growth. As part of the broader focus on leverage in the economy, officials warned that these large, heavily indebted conglomerates (the ‘grey rhinos’) needed to scale back leverage.

As a direct result of this, high profile Chinese conglomerates like HNA Group, Anbang Insurance and Dalian Wanda were forced to sell assets (including in Australia), in order to reduce debt.

These examples all point to a clear policy of deleveraging to reduce China’s reliance on debt fuelled economic growth.

While the end goal is sensible, the path to getting there is fraught, as authorities need to strike a fine balance between reigning in financial risks, but without completely cutting off the credit lifeline that many companies had become reliant on.

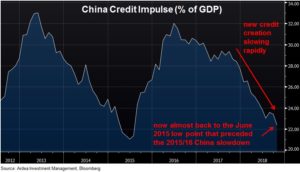

The effect of these and other similar deleveraging measure can be clearly seen in China’s credit impulse, which measures new credit creation as a percentage of GDP.

This measure is now back near the low point that preceded the 2015/16 economic slowdown that reverberated across global financial markets (the ASX200 dropped 20% over that period).

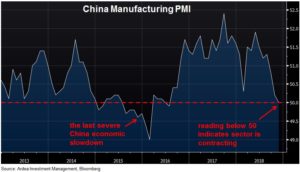

In a highly leveraged economy like China, access to credit is an important driver of economic growth. So it’s no surprise that economic growth indicators have weakened as credit conditions tightened. This has been particularly pronounced in the heavily debt reliant manufacturing sector, as shown in the chart below of China’s manufacturing PMI (a survey based measure of the sector’s health).

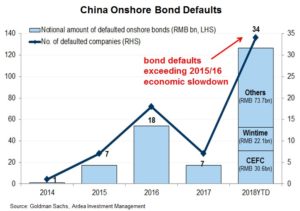

It’s also no surprise that the combination of tighter credit availability and slowing economic growth is causing debt default rates to increase.

While it’s standard procedure in more developed bond markets for creditors to risk losing part (or all) of their bond principal when borrowers get into trouble, China has historically resorted to a restructuring compromise that avoids capital losses for bondholders, often with government help.

This way of handling things kept default rates artificially low and hid the true state of financial distress among companies raising debt in the bond markets. But this is slowly changing.

Back in September 2017, Dongbei Special Steel Group bondholders agreed to a 78% loss on their principal, as part of a debt restructuring deal. This was the first time that Chinese creditors had publicly agreed to take a capital loss … from a government backed borrower no less.

Since then, debt default rates have been steadily rising, as Goldman Sachs recently reported;

“Despite recent efforts by China’s policymakers to increase the flow of credit to private enterprises, the pace of onshore bond defaults has not slowed. September 2018 was the heaviest ever month in terms of the number of new defaults in the China corporate bond market with seven issuers defaulting, and defaults have remained elevated with six new cases each in October and November.”

– Goldman Sachs, December 2018

Much has been written about unproductive investment and overcapacity in the Chinese economy (think ghost towns and bridges to nowhere), which has boosted reported GDP at the expense of a growing pile of debt.

Reported GDP doesn’t differentiate between productive investments that generate sufficient revenues to repay their debt and unproductive investments that don’t. So, to the extent that investors now start recognising losses via debt defaults, there will be a flow through to GDP numbers.

All these indicators point to a significant slowdown and growing stress in China’s economy… and this is all happening even before the effect of trade tariffs has really been felt.

As UBS reports on China’s most recent export numbers;

“November exports slid more than expected to 5.4%y/y, with across the board weakness… However, although around half of Chinese exports to the US have been subject to additional tariffs (25% tariff on $50bn goods, 10% tariff on $200bn goods), China’s exports to the US have not seen a big slowdown in recent months…”

– UBS, December 2018

Adding another layer of complexity is heightened political risk, particularly for China’s trading partners, as President Xi pushes ahead with his consolidation of power, the extent of which has not been seen since the era of Mao Zedong.

The Economist magazine (rather alarmingly) summed it up this way;

“Last weekend China stepped from autocracy into dictatorship. That was when Xi Jinping, already the world’s most powerful man, let it be known that he will change China’s constitution so that he can rule as president for as long as he chooses – and conceivably for life. Not since Mao Zedong has a Chinese leader wielded so much power so openly. This is not just a big change for China, but also strong evidence that the West’s 25-year bet on China has failed.”

– The Economist, March 2018

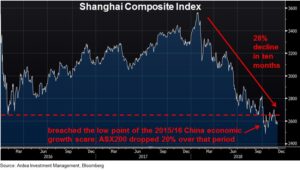

Having to contend with all of this at the same time, China’s equity markets have collapsed, as shown in the chart below.

Perhaps the best indicator of just how bad things have become is the extent to which Chinese authorities are going to stabilise the economy.

Earlier this year, bank stocks fell when the government took the unprecedented step of explicitly ordering banks to direct at least one third of all new loans to (riskier) private companies, rather than (safer) state owned enterprises, in order to improve credit availability for the struggling private sector.

More recently, senior policymakers and the President himself have been publicly talking up support for the economy in a way they have rarely done so before.

And in a sign of growing desperation, censorship of financial analysts and media has stepped up;

“Censorship has never been so tight, said one business journalist with two decades of experience. ‘There has been a big shift in the second half of this year.’

Chinese propaganda officials over the past few months have handed down instructions not to changshuai – bad mouth – the economy, according to a dozen journalists and editors at influential Chinese publications who spoke anonymously to the FT.”

– The Financial Times, November 2018

Expect to see more of both conventional and unconventional economic stimulus measures from China in the coming months.

The big question… will it be enough?