Central banks decide to keep the bar tab open

Bloomberg News recently ran this headline – “Two Epic Bull Markets Are Duelling over the Fate of Global Growth” – and went on to explain, “In the simplest terms, bonds investors are screaming recession, while equity and credit traders refuse to hear it.”

What they’re referring to is the seeming disconnect between bond and equity performance this year.

In a conventional analysis framework, when bonds rally in anticipation of weaker economic growth, equities tend to do badly. However, as shown in the table below, 2019 has seen significant rallies in both bonds and equities at the same time.

We referenced this theme in April, when we wrote;

“Conventional thinking about bond-equity relationships currently poses a paradox.

On one hand, this year’s sharp decline in global govt. bond yields, together with short dated interest rate markets in countries like the US and AU pricing in rate cuts, is interpreted by many as indicating a growing probability of recession.

On the other hand, equities globally are having one of the best Q1 rallies on record.”

In our view, it’s the actions of central banks that explain this seeming disconnect.

Specifically, back in January we noted how quickly central banks have been responding to even modest signs of financial market weakness and wrote about the distortionary effect this was having on risk pricing;

“We’ve highlighted previously that the combination of abnormally low interest rates and QE was akin to the bar tab that had kept the markets party going in the post financial crisis era and that it had clouded investor judgement on risk and asset pricing … near zero interest rates can make any asset look attractive.

And so it was that 2018 goes down as the year when the central bank bar tab finally ran out, causing a more sober evaluation of asset prices to re-assert itself.”

The bar tab running out was a reference to the events of 2018, when rising US interest rates and the cessation of bond buying via the US Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) program triggered the largest global equity drawdown since the 2008 financial crisis.

Things have since changed. Asset prices are once again in a festive mood at the prospect of central banks whipping out their credit cards to keep the financial markets party going. This is clearly evidenced by the extent to which bond markets are now pricing interest rate cuts.

As JP Morgan points out;

“The magnitude of rate cuts expected over the next 1-2 years ranges from around 10bp for the ECB and SNB to 15bp for the BoE and BoJ to around 50bp of rate cuts for BoC, RBA and RBNZ and 100bp for the Fed. It is thus striking how the market backdrop shifted from selective tightening to universal easing.”

– J.P. Morgan Flows & Liquidity Report, 10th June 2019

Returning to that Bloomberg headline, bond investors may not in fact be screaming ‘recession’ but rather anticipating the now familiar pattern of pre-emptive rate cuts that keep the asset prices supported.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, markets have become conditioned to a dynamic whereby, at the slightest hint of market volatility, central banks are quick to top up the monetary stimulus bar tab in order to keep the party going.

For financial markets, this is the best of both worlds … for now.

On one hand, the economic picture globally is not yet bad enough to cause serious recession fears but on the other hand, economic momentum has slowed just enough to bring the central bank stimulus dynamic back into play.

With interest rates and bond yields in most markets now back to record low levels, and indeed negative in many places, the question for both bond and equity investors right now is whether those central bank credit cards will have already hit their limits by the time they’re really needed to get economies out of a serious bind.

A growing body of research suggests that when interest rates are already very low, cutting them further or engaging in other forms of monetary stimulus becomes less effective in stimulating economic growth. For example, a 2017 research paper from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) noted;

“The empirical evidence relating to these questions is rather scant. That said, what is available suggests that monetary policy transmission is indeed weaker when interest rates are persistently low. The economic context appears to matter, making it more likely that policy may push on the proverbial string as headwinds blow.”

– Reserve Bank of Australia

Looking forward, this leaves markets in a tenuous balance.

The extent of pre-emptive rate cuts that are currently priced in (especially in the US) looks aggressive and can only be justified in a very negative economic scenario. However, if such a scenario were to materialize, it could end up being quite bad for stocks, even if those rate cuts do materialize.

The alternative is a less dire economic path, but one that causes bond markets to walk back the extent of rate cuts currently priced in, leading to a potentially violent re-pricing of bonds as yields are forced higher to more realistic levels. As the experience of 2018 showed, that kind of bond market volatility is generally not good for stocks either.

The other issue is unintended side effects. On that point, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has been running its bar tab longer than any other central bank, which makes recent comments from BOJ Governor Kuroda worth heeding.

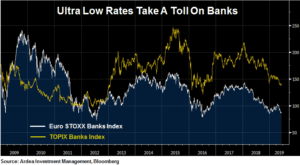

In a Bloomberg TV interview this month he talked about the risky side effects of the BOJ’s extreme monetary stimulus program, which has kept Japanese interest rates at negative levels for many years now and has also left the BOJ owning large chunks of Japanese bond and equity markets. In particular, he singled out the negative side effects on Japan’s banks, who are struggling to cope with skinnier net interest margins, as rates keep going lower.

With interest rates increasingly negative across Europe as well, the same dynamic is taking a toll on European bank profitability as well.

While broader stock market indices are reaching new record highs, bank stocks in Europe and Japan have fared poorly, as shown in the chart below. This is of course topical for Australian banks as the RBA has now joined the global rate cut club.

More generally, continually extending the bar tab in the way central banks are currently doing means the morning after hangover could be a particularly painful one.