The changing role of duration in an ultra-low yield world

In this article we explore the following topics:

- The market backdrop of ultra-low government bond yields

- The use of duration as a portfolio risk diversifier

- Why the starting point of bond yields matters a lot

- Unstable bond vs. equity correlations

- The questionable safe haven assumption of passive government bond investments

- Duration as portfolio insurance

- The changing role of duration in multi-asset portfolio construction

(Please note, the ideas in this article are most relevant for conventional balanced portfolios and less relevant for special use cases of duration such as matching liabilities.)

Introduction

Conventional government bond investments, with their inherent interest rate duration exposure, have long been the defensive anchor of choice for multi-asset investment portfolios seeking a balanced risk profile. That approach is no longer optimal.

Ultra-low yields fundamentally change the risk vs. reward proposition of government bonds and therefore challenge conventional assumptions about the defensive role they are supposed to play in a broader portfolio.

With the starting point of government bond yields already close to zero, duration can no longer provide the same upside to offset equity losses that it used to. Even worse, duration exposure has become much riskier in its own right, as its risk vs return profile has become unfavourably asymmetric.

Many portfolios use conventional duration based government bond investments as a kind of portfolio insurance; basically something that can do well when equities fall. Viewed through this lens, duration is now a very expensive insurance policy that can no longer pay out as much as it used to; and in a growing range of scenarios it may not pay out all when needed most.

The conclusions here are not binary. Duration exposure is not inherently good or bad. Nor is it a question of whether it should or should not be excluded entirely. Rather, it’s a more nuanced re-assessment of how duration exposures might behave in different scenarios and an objective scrutiny of how reliably duration exposure can continue to play its defensive risk diversification role.

While duration can still provide some incremental diversification benefit vs. equity risk, its best days are gone. Those days will return when bond yields rise again, but until then it is unrealistic to expect duration to provide anywhere near the benefits that it used to. As such, there is now a stronger incentive to search for other sources of genuinely defensive risk diversification. Equally, the potential costs of inaction have also increased.

Looking backward, conventional duration has worked well. However, forward looking investors are now re-assessing their past assumptions and showing a greater sense of urgency in looking beyond the conventional for the defensive parts of their portfolios.

There are other lesser known but increasingly compelling options, which have repeatedly proved that fixed income investments do not need interest rate duration to provide reliable diversification and downside protection against equity risk.

The market backdrop

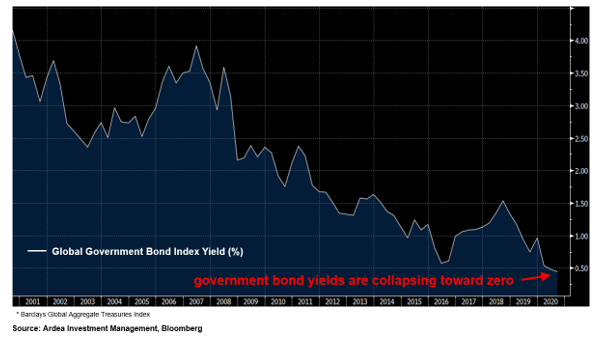

Central banks have responded to the COVID-19 crisis by aggressively cutting interest rates, leaving policy rates in most major economies now hovering around 0%. Consequently, government bond yields in most places are also fast approaching zero, while a growing proportion are actually negative.

While nobody can reliably predict which way interest rates and bond yields will head in the future, it is clear that ultra-low bond yields have immediate implications for portfolio construction today.

With the starting point of bond yields already near zero, the oft used disclaimer that past performance is not indicative of future performance comes to mind because the duration exposure inherent in government bonds can no longer provide the same protection against equity sell-offs that it used to. This in turn has left conventional duration based government bond investments severely limited in their ability to act as defensive anchors in multi-asset investment portfolios.

This is a theme we have covered many times before, and it is now getting more mainstream attention.

“The staple U.S. portfolio of 60% equities and 40% fixed income proved resilient this year, but strategists are now considering alternatives to government debt after some bond yields reached historic lows.

… ‘I don’t think bonds can provide the standard historical returns investors are used to,” said Andrew Sheets, Morgan Stanley’s chief of cross-asset strategy in London. ‘The starting yield is at a point where that type of return is just not possible. Investors are going to have to lower expectations of 60-40 portfolios and will have to look elsewhere for what can be in the 40%.’ Blending stocks and bonds, a decades-old investment staple to balance risk and reward, is being tested by ultra-low yields.”

– Bloomberg, ‘Investors Rethink ‘60/40’ as Ultra-Low Yields Test Portfolios’, 2nd August 2020

“Covid-19 has brought us to a historic turning point in financial markets. A fundamental investment strategy that has protected institutional and retail investors alike for decades — balancing equity risk by holding high-quality government bonds — has finally run its course.

When the Fed lowered short-term rates to zero in response to the pandemic, the last shoe dropped. The implications of this change are huge. For one thing, millions of retail investors have been left largely defenceless, lacking a tried and tested means of diversifying the inevitable risk of holding equities.”

– Financial Times, ‘Collapsing rates leave investors dangerously exposed to equity risk’, 8th June 2020

Duration as a portfolio risk diversifier

The interest rate duration exposure inherent in conventional government bond investments has long been the go-to risk diversifier of choice for multi-asset investment portfolios seeking a balanced risk profile.

Think back to the 2008 financial crisis. While equities and other risky assets collapsed, interest rates and government bond yields also fell, as central banks cut interest rates aggressively. This in turn caused government bond prices to skyrocket, delivering handsome profits to those holding government bonds as defensive portfolio anchors. Those profits helped offset losses elsewhere in their portfolios, thereby dampening overall portfolio performance volatility and limiting the severity of total portfolio level drawdowns. This is the negative correlation effect that has historically provided the strongest diversification benefit from government bonds when it was needed most.

As it was duration exposure that linked falling bond yields to rising bond prices, it was duration exposure that was they key source of portfolio risk diversification and this remains the central diversification assumption on which conventional balanced portfolio construction still relies. (A refresher on bond yields and interest rate duration is available here.)

Aside from this negative correlation effect, the generally lower volatility of government bonds vs. equities also provides some risk diversification benefits. However, the strongest benefit comes from both working together.

Looking backward, we can point to other episodes like 2008 where the assumption that duration protects against downside equity risk has indeed worked well. But looking forward, this assumption is less reliable because the starting point of bond yields matters a lot. With government bond yields collapsing toward zero it is unrealistic to simply assume that duration can keep providing the same portfolio risk diversification benefits it has in the past. Additionally, there is the problem of unstable bond vs. equity correlations.

“For much of the past century, the building blocks of most investment portfolios have been a combination of riskier stocks and steadier, safer bonds. Like a see-saw, one typically rises if the other falls, smoothing returns and offering a hedge.

But over the past decade, this relationship has broken down. Bond yields have sagged as their prices have risen alongside equities, producing healthy gains but limiting how much protection bonds can offer in downturns. The recent market chaos unleashed by the coronavirus pandemic has underscored the problem, with bruising trading periods in which bonds and equities have dropped in unison.”

– Financial Times, ‘Market ructions test faith in classic portfolio mix’, April 2020

The starting point of bond yields matters a lot

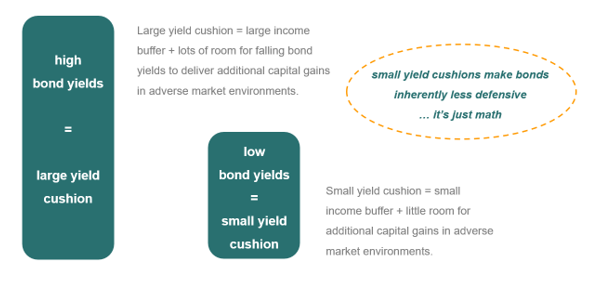

In the context of portfolio risk diversification, we can think of the stable income provided by government bonds, together with the potential for declining bond yields to deliver additional capital gains, as a yield cushion that helps offsets losses on equities and other risky assets in adverse scenarios.

When the starting point of bond yields is higher, yield cushions are larger, which means bonds can do a good job of playing this risk diversification role. But when the starting point of bond yields is already very low to begin with, the diversification value of bonds is compromised.

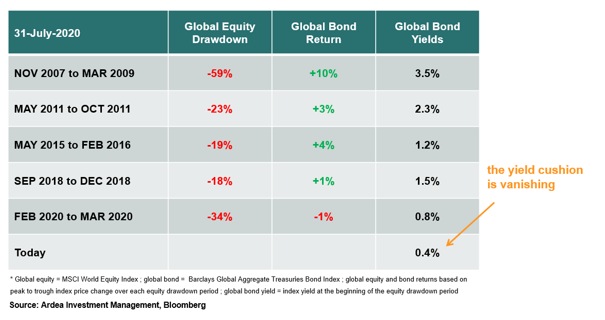

As an example, heading into the 2008 financial crisis interest rates and bond yields were much higher than they are today, meaning yield cushions were large. Consequently, there was a lot of room for government bond yields to fall and therefore for their prices to rise, resulting in large bond profits that helped offset equity losses. As such, the duration exposure inherent in government bonds did a great job of dampening overall portfolio losses. However, as the table below shows, over subsequent equity drawdown periods this loss dampening effect progressively eroded away as yield cushions shrunk toward zero.

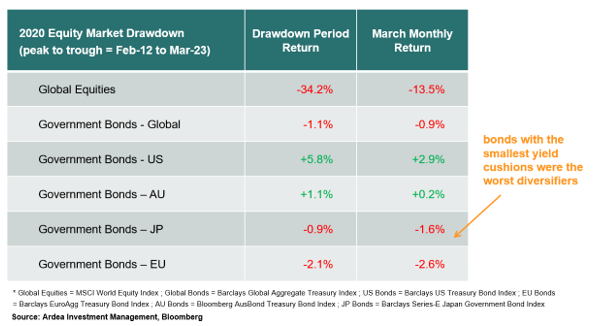

In fact, over the Q1 2020 period – the most severe global equity drawdown since 2008 – we can see that the widely followed Barclays global government bond index actually delivered a negative return over the equity drawdown period.

Drilling down to some of the individual government bond markets, it’s not a coincidence that the bonds with the smallest yield cushions – i.e. the lowest starting point of yields – did the worst job of diversifying equity risk.

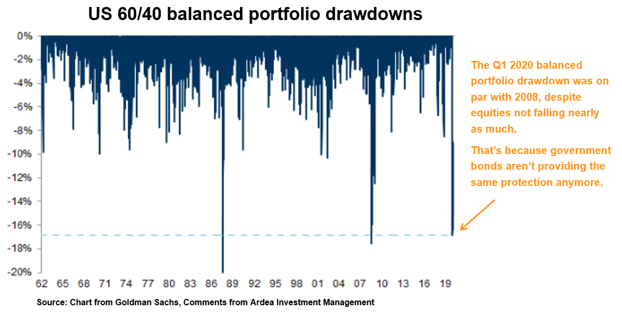

Even in the US, where there was at last some yield cushion to begin with, the diversification value of government bonds was not nearly as good as it has been in the past. This is shown in the chart and commentary below, which refers to the performance of a stereotypical 60/40 balanced portfolio that attempts to diversify equity risk by adding conventional government bond duration exposure.

“A 60/40 portfolio had one of the largest drawdowns since the 1960s this month. This was due to the sharp equity drawdown but also as there was less of a buffer and diversification from bonds.

… In addition to the sharper-than-normal equity correction, diversification in 60/40 portfolios has been less good. First, with bond yields at all-time lows now and close to the effective lower bound, there is little space for most DM bonds to buffer equity drawdowns. In other words, the beta of bonds to equities has declined, especially in Europe and Japan. But also equity-bond correlations turned positive in most markets” (note: DM = developed market)

– Goldman Sachs, ‘The 60/40 Drawdown and Multi-Asset Portfolio Risk’, Mar 2020

There are a few remaining government bond niches with meaningful yield cushions (e.g. 20+ year US or Australian government bonds that still have >1% yields). However, they require investors to take a lot more duration risk just to have a chance of decent upside when equities fall. In doing so, investors are forced to tolerate an increasingly unfavourable standalone risk vs. return profile because even a modest normalisation of rates toward historical averages would leave 20+ year bonds with large losses.

There is an added complication because, by definition, longer duration bonds come with more price volatility (explained here). For example, the longer duration Barclays 20+ year US government bond sub-index experiences c. 3x the price volatility of the broader index, which includes lower volatility shorter dated bonds.

This trade-off puts investors in a bind because the lower volatility of government bonds vs. equities is supposed to be one of their main diversification benefits. Therefore, if investors stretch for longer duration bonds to maintain at least some yield cushion, they simultaneously lose much of the low volatility diversification benefits that their government bond allocations are supposed to provide.

Away from these long duration niches, the only way that broad government bond index duration exposure can provide a meaningful cushion against future equity drawdowns is if index yields go negative. For example, the same US government bond index that returned 5.8% over the Q1 2020 equity drawdown, would need to hit a yield of -0.3% to repeat that performance. While that is possible, it is hardly an assumption one wants to rely on, particularly given the growing recognition that negative interest rate policies have adverse side-effects (discussed here).

With the starting point of bonds yields already so low, it is unrealistic to expect conventional government bond duration to provide anywhere near the risk diversification benefit that it used to. As a wise colleague said:

‘The duration lemon has already been squeezed hard. How much juice is left?’.

Bond vs. equity correlations are unstable

In a prior article we outlined the main attributes via which an investment can help diversify equity risk in multi-asset portfolios. Among them, correlation is an important one. (A refresher on correlation concepts is available here and here.)

Introducing investments with low equity correlation will reduce total portfolio volatility, even if those investments are still positively correlated with equities. However, the strongest diversification benefit comes from negatively correlated investments because they are most likely to deliver positive returns when equities fall and will therefore have the strongest total portfolio volatility dampening effect.

In that same diversification article, we also noted that consistency of behaviour is an important consideration. For example, an investment that exhibits low or negative equity correlation in benign market environments but then exhibits strongly positive equity correlation when equities fall is not an effective diversifier.

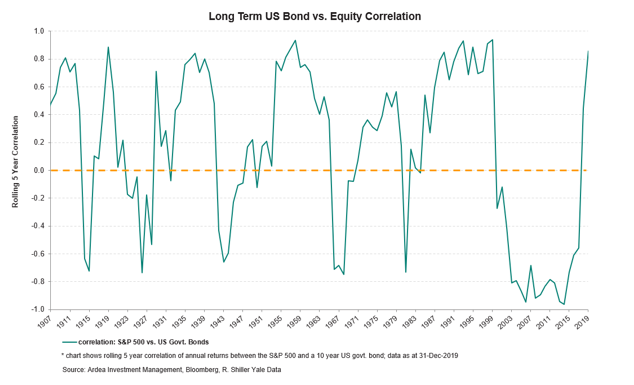

Back during the 2008 financial crisis, high quality government bond returns did indeed exhibit strong negative equity correlation (i.e. bond prices rose as equities fell). However, as we explained in another prior article, the correlation between bonds and equities is inconsistent because it is impacted by shifting macroeconomic themes such as central bank policy, fiscal policy and inflation expectations. For example, the chart below shows how variable the long term US government bond vs. equity correlation has been.

Looking forward, three interrelated macroeconomic themes could drive a paradigm shift to more persistently positive bond vs. equity correlations. First, the now pervasive link between ultra-low interest rates and asset valuations; second, the widespread expectation that inflation is unlikely to rise materially above central bank target ranges; third the extraordinary fiscal stimulus currently being rolled out.

The ‘lower for longer’ paradigm – i.e. the expectation for ultra-low rates + subdued inflation to persist for a long time – has been used to justify stretched valuations everywhere from equities to bonds to property. Related to this, the TINA narrative (i.e. There Is No Alternative) explains the immense ‘reach for yield’ dynamic whereby a wall of money has been progressively moving into riskier assets in search of higher returns as interest rates kept falling … ultra-low interest rates can make any asset look attractive, regardless of its risks. (details here and here)

This in turn has created a positive correlation dynamic between interest rates / bonds yields and equity prices because anything that threatens the low rates / yields status quo – for example unexpectedly higher inflation or concerns about excessive government spending – would be negative for both bonds and equities. (details here and here)

The prospect of a paradigm shift in bond vs. equity correlations is a subject Morningstar tentatively broached earlier this year (see here)

“Nevertheless I think we should at least consider the possibility that the long-standing stock-bond relationship may be ending.

… given the extraordinary amounts of cash that global central banks have created in recent years, inflation may resurface. Not, one fervently hopes, as ferociously as it did during the 1970s. But nothing so dramatic would be required to reduce, if not eliminate, long bonds’ diversification benefit. Even the hint of higher future interest rates would harm both equities and long Treasuries, thereby more closely aligning their returns.

Or, inflation will remain dormant, but the relationship between equity and bond returns will nonetheless change for the intermediate term because the economic levers have shifted.

… If that is the case, four decades’ worth of asset-allocation advice will need to be altered.”

– Morningstar, ‘Will Stock and Bond Performance Converge?’, 19th May 2020

As Peter Bernstein reminisced in an interview with the Wall Street Journal’s Jason Zweig (available here), when genuine paradigm shifts happen, they take investors by surprise because expectations of the future are so skewed by experiences of only the recent past.

Zweig: You’ve often written that something important happened in September 1958. What was it?

Bernstein: [For the first time in history,] stocks began to yield less than bonds, and it was not something tentative. The lines crossed without any period of hesitation and just kept on going. It was just, zzzoop! All my older associates told me that it was an anomaly and it could not last. To understand why that happened and what that meant — and to recognize that what was accepted wisdom for a couple hundred years could turn out to be wrong — was very important. It really showed me that you don’t know. That anything can happen. There really is such a thing as a “paradigm shift,” when people’s view of the future can change very dramatically and very suddenly. That means that there’s never a time when you can be sure that today’s market is going to be a replay of a familiar past.

Markets are shaped by what I call “memory banks.” Experience shapes memory; memory shapes our view of the future.”

To borrow Bernstein’s terminology, investor ‘memory banks’ today are highly influenced by the post-2008 experience of falling rates and low inflation. As such, portfolio construction frameworks, asset allocations, valuation models etc. have become highly skewed to this ‘lower for longer’ paradigm continuing.

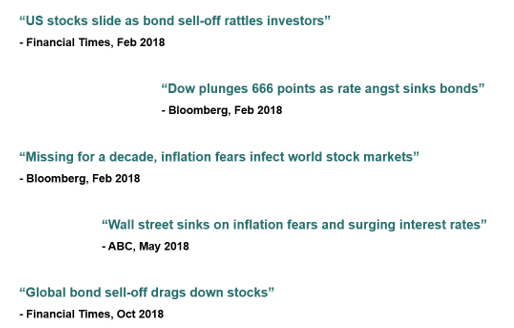

Consequently, even an inkling of the prospect of a shift away from the ‘lower for longer’ paradigm can cause turmoil. This is exactly what happened in 2018 when rising US interest rates, together with the prospect of higher inflation, caused bond market volatility, which then spilled over into equities. Investor memory banks that were conditioned to think of government bonds as a safe haven, as the defensive risk diversifier for equities, got a rude shock when bonds themselves became the catalyst for the equity market turmoil.

Tying all this together, there is now too much ‘decision risk’ in pinning an entire portfolio risk diversification strategy on the single assumption that government bonds and equities will remain negatively correlated.

Passive government bond investments are no longer the safe haven they used to be

Assumed to be inherently low risk, high quality government bonds have long played the defensive ‘safe haven’ role in multi-asset investment portfolios and passive bond funds have provided a cheap and effective way to get this exposure.

From a credit risk perspective, that safe haven assumption generally still holds, but interest rate risk is a different story because ultra-low bond yields fundamentally change the risk vs. return proposition of government bonds. While passive government bond investments may be cheap from a narrow fee perspective, they are no longer good value in terms of their risk vs. return profile.

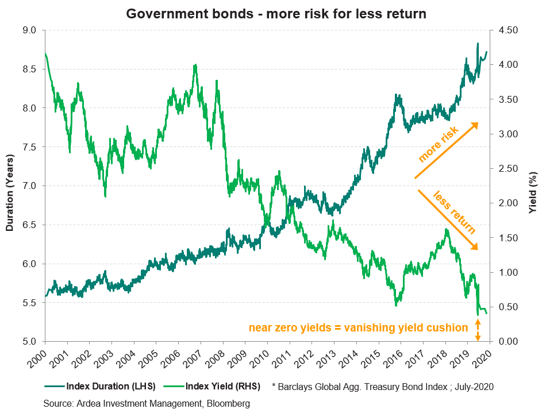

Focusing on the standalone risk vs. return profile of government bonds, investors earn the interest income paid by those bonds (i.e. yield) in exchange for the risk of bond prices falling if interest rate rise (i.e. interest rate duration risk). As bond yields represent the compensation that investors receive for bearing interest rate duration risk, we can look to the duration vs. yield trade-off as a good indicator of how attractive (or not) the risk vs. return proposition is.

The chart below shows the evolution of this risk vs. return trade-off for a typical global government bond index that a passive bond fund might track. As bond yields have collapsed toward zero, while interest rate duration risk has increased, passive bond investments have been left facing a lot more risk, for a lot less return.

Of course, duration risk works both ways. If bond yields fall a lot, as they have historically done, duration exposure can deliver large price gains as well. However, with government bond yields already close to zero, the potential for history to repeat has greatly reduced. This means the duration risk inherent in passive government bond investments has become unfavourably asymmetric i.e. the future loss potential has become disproportionally large relative to the remaining upside.

2018 gave us just a small taste of the downside risk inherent in ostensibly ‘safe’ passive government bond investments. For example, that same government bond index referenced in the chart above, had a drawdown of c. 7% over 8 months and the longer duration iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF was hit with a c.13% drawdown.

This kind of volatility might be acceptable if the commensurate upside potential was also there. However, the unavoidable reality is that bond prices can’t keep going higher unless yields keep going lower. With yields now already so close to zero the future upside potential has eroded away, leaving the risk in duration exposure heavily skewed to the downside.

As equity investors know well, the price at which you buy matters as much as what you buy. Government bonds are not immune from losses if you buy at too high a price. While the future direction of bond markets is unknowable, what is clearly visible right now is that the risk vs return profile of conventional duration-based bond investments has become unfavourably asymmetric.

We covered this theme in more detail here and the tail risk scenario of a violent sell-off in government bond markets here.

As the wider debate on active vs. passive management rages on, it is not a simple binary choice when it comes to government bonds. Passive bond funds offer a cheap, reliable and easily understood way to access beta exposures like duration, which can be an important part of the toolkit for multi-asset investment portfolio construction. At the same time, we must acknowledge that duration is a blunt instrument that doesn’t work so well when the starting point of bond yields is already very low.

Cheap passive exposure to duration beta can be attractive when it offers an acceptable risk vs. return proposition and can reliably play a portfolio role. Failing that, it is a false economy. Passive duration exposure will become more useful again when yields rise meaningfully but until then it no longer reliably plays that defensive ‘safe haven’ role for multi-asset portfolios.

Duration as portfolio insurance

The duration vs. yield chart in the previous section shows the worsening standalone risk vs return characteristics of interest rate duration exposure (i.e. more risk for less return). Some may be willing to overlook this because of the portfolio ‘protection’ role they hope government bonds might still play; as something that can help reduce total portfolio level drawdown risk by doing well when equities fall.

Given equity beta tends to be the most dominant risk factor in multi-asset investment portfolios, investments that tend to perform badly in adverse environments are likely to incur losses together with equities and are therefore risk additive to a portfolio. As such, investors should demand higher risk premia to hold them i.e. investors should only be willing to buy them at lower prices, with higher future return potential.

Conversely, investments that tend to do well when equities fall are risk reducing because they help to offset equity losses in the bad times, thereby dampening overall portfolio volatility. These investments should warrant lower risk premia i.e. investors should be willing to buy them even at higher prices, with lower future return potential. This is the conventional justification as to why it can still be rational for investors to hold government bonds, even when their return potential is very low.

However, there are limits to this argument, and in this context we can think of the duration exposure inherent in government bonds as a form a portfolio insurance. Using this analogy, the cost of the duration ‘insurance policy’ is implicitly reflected in the standalone risk vs. return proposition of holding duration exposure, while the payout is the upside potential of government bonds in the event of a large equity sell-off.

As with any insurance policy, it’s important to understand whether it offers good value for money. Is it reasonably priced relative to what it can pay out when needed?

Starting with the implicit cost of the duration insurance policy – i.e. the standalone risk vs. return proposition of holding government bonds – we can break it down into two components, from which we conclude that this is currently a pricey insurance policy:

- Low expected returns: Government bonds generally have lower expected returns than equities. Therefore, holding them imposes a return drag on the portfolio. This component of the cost is unusually high right now because ultra-low government bond yields mean very low (or even negative) expected returns from holding government bonds.

- Asymmetric duration risk: As government bond prices fluctuate because of their duration exposure, they can impose losses on a portfolio. As discussed in the previous section, the current asymmetry of duration risk means this component of the cost is also currently high.

Having evaluated the cost of the duration insurance policy, we also need to consider how much it can pay out when needed. A pricey insurance policy may be justifiable if the potential payout is sufficiently large.

Unfortunately, the vanishing yield cushion in government bonds means the insurance policy can no longer pay out very much. We discussed this in the earlier section titled – ‘The starting point of bond yields matters a lot’.

Paying for insurance makes sense when the policy is reasonably priced and can reliably protect you when you need it. With government bond yields already near zero, the duration insurance policy is failing on both accounts. It is expensive and can no longer pay out very much. Even worse, it may not a pay out at all in a growing range of scenarios, as we discussed in the earlier section titled – ‘Bond vs. equity correlations are unstable’.

Implications for multi-asset portfolio construction

The conclusions here are not binary. Conventional duration based government bond investments are not inherently good or bad. Nor is it a question of whether they should or should not be excluded from multi-asset portfolios entirely.

Rather, what’s required is a more nuanced re-assessment of how duration exposures might behave in different scenarios and an objective scrutiny of how reliably duration exposure can continue to play its defensive risk diversification role.

We’re in an environment that fundamentally changes the risk vs. reward proposition of conventional duration based bond investments and challenges conventional assumptions about the diversification value of including them in multi-asset portfolios. These are not temporary blips; they are a paradigm shift driven by the vanishing yield cushions offered by government bonds and the increasingly unfavourable asymmetry of their inherent duration risk.

While duration can still provide some incremental diversification benefit vs. equity risk, its best days are gone. Those days will return when bond yields rise again, but until then it is unrealistic to expect duration to provide anywhere near the risk diversification benefit that it used to.

While there is still a role for duration beta exposure in multi-asset portfolios, particularly because it’s easy to understand and cheap to implement, it is a blunt instrument that works best when the starting point of bond yields is reasonably high. Given we’re in precisely the opposite environment right now, it is sub-optimal to be overly reliant on duration for diversification and downside protection vs. equity risk.

By extension, we need to question whether duration beta exposure still deserves its position as a core portfolio building block or whether it should be temporarily relegated to a supporting role until interest rates rise and government bonds regain their yield cushions.

There is a further consideration that is specific to the current environment. Namely, a range of tail-risk scenarios stemming from the unprecedented fiscal plus monetary stimulus combination currently being implemented around the world. The kinds of tail-risks that could make long duration government bonds yielding sub-1% look as absurd as junk bonds trading with negative yields already do. (details here)

Tying all this together, the incentives to look beyond the conventional duration lever to find other sources of genuinely defensive risk diversification are increasing, as are the potential costs of inaction.

While few are abandoning duration completely, we are seeing more forward looking investors re-assessing their past assumptions and showing a greater sense of urgency in looking beyond the conventional for the defensive parts of their portfolios.

There are other lesser known but increasingly compelling options, which have repeatedly proved that fixed income investments do not need interest rate duration to provide reliable diversification and downside protection against equity risk.

This material has been prepared by Ardea Investment Management Pty Limited (Ardea IM) (ABN 50 132 902 722, AFSL 329 828). It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Any projections are based on assumptions which we believe are reasonable, but are subject to change and should not be relied upon. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Neither any particular rate of return nor capital invested are guaranteed.