Market inefficiency is a growing opportunity in fixed income

In this article we explore the following themes relating to fixed income market inefficiency:

- why fixed income markets are persistently inefficient

- why this inefficiency is a reliable source of returns

- the growing opportunity for investors to profit

Why does market (in)efficiency matter?

When the pre-eminent economist Fischer Black (of ‘Black-Scholes option pricing model’ fame) left academia to join a Wall Street fund management firm, he famously observed “…the market appears a lot more efficient on the banks of the Charles River than it does on the banks of the Hudson.”

Black was contrasting the academic view of efficient markets from the Charles River in Boston, where he had spent most of his working life at universities, to the real-world market practitioner’s view from the Hudson River in New York.

In the years preceding Black’s comment, numerous academic theories from economics and finance were developed around the idea of market efficiency. Ranging from the ‘efficient markets hypothesis’, to the ‘law of one price’ and ‘arbitrage pricing theory’, they were all based around the basic proposition that asset prices in efficient markets reflect all relevant available information and by extension, that two assets with the same expected risk should be priced consistently with one another.

The argument was that if these conditions failed to hold, investors could generate risk-free profits by exploiting any pricing inconsistency through a process called ‘arbitrage’. It was therefore assumed that arbitrageurs seeking risk-free profits would always keep markets efficient as their buying and selling activities quickly forced those inconsistent prices back into line, generating handsome profits for themselves in the process.

As Black’s observation alluded to, in the real world things don’t always work as efficient market theorists assumed and therefore market inefficiency is a reliable source of alpha that investors with the right expertise can exploit to generate attractive risk-adjusted returns.

Why are fixed income markets inefficient?

The efficient market theories mentioned above all rely on the underlying assumption that market participants act rationally, with the objective of maximizing risk-adjusted returns and without any frictions preventing them from achieving this objective.

In the real world these assumptions often don’t hold, which is what prompted Black’s observation on the contrast between theory and practice.

For fixed income in particular, the varying objectives of market participants and the practical frictions they encounter, are important structural factors that prevent market inefficiencies from being quickly arbitraged away. The sheer diversity of participants in fixed income markets, all working with different objectives and constraints, causes fixed income to persistently exhibit more inefficiency than other large asset classes such as equities and FX.

Compared to equities, fixed income has a greater diversity of market participants regularly buying and selling a huge variety of different bonds (and related interest rate derivatives) for reasons other than maximising profits.

We can classify them as ‘non-economic’ market participants, and they have the following characteristics:

- they are not necessarily motivated to maximise risk-adjusted returns

- it can be rational for them to transact at prices that are inconsistent with efficient market pricing because they are pursuing other objectives

- they are subject to internal and external constraints that can compel them to transact at prices materially deviating from objective fair value

Examples include banks managing their balance sheets, governments financing budgets, passive investors tracking benchmarks, insurance companies matching liabilities, central banks pursuing policy objectives and those engaging in general interest rate risk management.

These non-economic flows (i.e. buying and selling activity) are very large and can dominate fixed income markets.

For example, in relation to interest rate derivatives, which account for the majority of annual turnover across global fixed income markets, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) notes the following:

“Over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives play a very important role in the risk management strategies of many firms.

Whether used by global corporates to eliminate exchange-rate risk in foreign currency earnings, by pension funds to hedge inflation and interest-rate risk in long-dated pension liabilities, or by governments and supranationals to reduce interest-rate risk on new bond issuance, OTC derivatives allow end users to closely offset the risks they face and to ensure certainty in financial performance.

Publicly available data published by the Bank for International Settlements reveals that 65% of over-the-counter interest rate derivatives market turnover involves an end user on one side and a reporting dealer on the other.

These participants, comprising nondealer financial institutions and non-financial customers, use derivatives primarily to hedge risks and reduce volatility on their balance sheets.”

– ISDA Research, ‘Dispelling myth: end-user activity in OTC derivatives’, August 2014

The large flows of these non-economic participants repeatedly create temporary demand-supply imbalances across various segments of fixed income markets. This in turn causes the prices of related securities, with very similar risk characteristics, to move inconsistently with each other, thereby violating efficient market principles.

These inefficiencies even exist across extremely large and liquid short term money markets, which are a segment of the fixed income market that effectively forms the plumbing of the global financial system.

Trillions of dollars flow through money markets daily as a diverse array of market participants borrow and lend cash for short periods, effectively setting the price of cash in each currency. If markets were efficient, that price would be consistent across all the various instruments that trade in money markets. However, in practice these prices are persistently inconsistent.

Australia’s central bank explains it this way in relation to AUD money markets specifically, but the same dynamics occur globally:

“In recent years, the spread between money market interest rates has widened. One implication is that the price of Australian dollars diverges across these markets. Even after risks associated with creditworthiness, liquidity and other factors have been taken into account, it appears that unexploited arbitrage opportunities persist.

… If markets are efficient and the risk characteristics of financial instruments are taken into account, there is no reason why the price of Australian dollar cash should differ across markets; that is, the law of one price should hold.

Under these conditions, market participants would exploit deviations in interest rates if they represent a profit opportunity by borrowing in the market where rates are lowest and lending to the market where rates are higher, until it is no longer profitable to do so.

In recent years, however, interest rates in short-term money markets have significantly and persistently deviated from each other”

– Reserve Bank of Australia, ‘Australian money market divergence: arbitrage opportunity or illusion?”, September 2019

In theory, these pricing inconsistencies should disappear quickly as arbitrageurs pounce to profit and force prices back into line by selling where there is excess demand and buying where there is excess supply.

In practice, there are significant frictions that prevent active capital from so seamlessly arbitraging away these temporary demand-supply imbalances. These include balance sheet restrictions, mark-to-market sensitivity, internal rules, external regulation, operational hurdles, lack of expertise and lack of incentives.

These real-world frictions mean that such pricing inconsistencies can occur repeatedly and last for prolonged periods, which is evidence of persistent fixed income market inefficiency.

A 2018 research report from the US central bank explained it this way:

“The law of one price – that the same exposure to the same source of risk should be priced the same no matter how that exposure is achieved – is one of the fundamental tenets of finance.

Prolonged periods when prices of related assets deviate from each other suggest limits to arbitrage: failures of the law of one price represent profitable trading opportunities that would be exploited by unconstrained institutions.”

– Federal Reserve Bank of New York, ‘Bank-Intermediated Arbitrage’, July 2018

Why is fixed income market inefficiency a reliable source of returns?

When most active fund managers talk about market inefficiency, particularly in equities, they are usually referring to informational and analytical inefficiencies. The idea is that new information is not always efficiently reflected in stock prices, either because many investors don’t access the information, or they don’t analyse it effectively to work it out what it means for stock valuations.

While these kinds of inefficiencies do still exist, they can be competed away as information flow is becoming increasingly democratised. For example, five years ago an active stock picker using satellite images to track traffic volumes in a retailer’s carpark could gain a competitive edge in forecasting sales. Today, that kind of data is readily available to anyone willing to pay for it.

By contrast, the underlying drivers of fixed income market inefficiency described earlier are far more structural in nature and most importantly, don’t result in a zero-sum game.

These structural drivers, such as externally imposed regulation, create buying and selling flows that are not motivated by profit. For example, as noted earlier, 65% of trading across interest rate derivatives, which account for the majority of annual turnover across global fixed income markets, relates to hedging of risks rather pursuit of profit.

These large non-economic flows are structural in nature and therefore persistent, which is what makes the mispricing they create a reliable source of returns.

The buying and selling flows of these non-economic participants has always been much larger than the pool of investors actively seeking to exploit market inefficiency, which is why these opportunities aren’t easily competed away. This imbalance has become even more pronounced since 2008 as bank balance sheet constraints have greatly restricted the arbitrage activities of bank traders.

Importantly, given these non-economic market participants have different objectives, it can be perfectly rational for them to keep buying and selling securities at prices that deviate materially from fair value. In this sense the tension between non-economic participants who create market inefficiency and those who seek to exploit it is not a zero-sum game. Both parties on opposite sides of the same trade can simultaneously achieve their objectives.

For example, insurance companies are large buyers of bonds, which they often hold to maturity. Their objective is to lock in a certain yield level that allows them to meet future obligations on the insurance policies they have sold (known as liability matching). It is rational for them to keep buying bonds, even if those bonds are obviously mispriced relative to other closely related securities (e.g. interest rate futures contracts), as long as the yield level is sufficient for them to match their liabilities.

Meanwhile, an active investor can arbitrage this mispricing and profit when the bond price moves. The insurance company on the other side of this trade is unaffected because they are still achieving their liability matching objective.

The sheer diversity of market participants, with varying objectives and constraints, trading across a huge variety of different security types has always been a key feature of fixed income markets that make them particularly fertile territory for exploiting market inefficiency. All of them are acting in ways that make sense for them individually, while at the same time contributing to flows that in aggregate create temporary demand-supply imbalances, which in turn causes pricing inefficiencies.

While individual pricing inefficiencies manifest in many different ways and specific inefficiencies can diminish over time as market conditions change or active investors exploit them. The underlying structural drivers are persistent, which means new opportunities keep getting created.

It is for these reasons that evidence of inefficiency dates back to the inception of fixed income markets and ever since has proven to be persistent over time and across market cycles. This persistence is what makes market inefficiency a reliable source of returns around which a repeatable investment process can be built.

The opportunity for investors is growing

The dynamics described above are not new. The underlying structural drivers of fixed income market inefficiency have been around since markets first existed. For example, regulations always have and always will influence the behaviour of market participants.

What has changed since 2008 is the size and availability of the opportunity for investors to access, which is due to structural changes in the banking industry.

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis most of the pricing inefficiencies were captured by the large fixed income trading operations of global investment banks. With huge unconstrained balance sheets, low cost of capital and plenty of specialised resources, they were ideally placed to generate profits by intermediating the temporary demand-supply imbalances that caused mispricing and had been dominating this space since as far back as the 1980’s.

The dominance of banks meant that many of these opportunities were captured on bank balance sheets before they could actually manifest openly across fixed income markets and therefore were never available for investors to access.

The 2008 crisis changed everything. The onerous regulations, balance sheet constraints and rising cost of capital that have smothered banks since 2008 have severely restricted their ability to keep capturing these opportunities. As a direct result, there are now more of these opportunities available and far less competition to access them:

- banks are now less willing and able to intermediate temporary demand-supply balances, resulting in more frequent and larger instances of inefficiency driven mispricing

- as these mispricing’s occur, banks are less able to capture them, meaning more of the opportunity set is now available for other investors to exploit

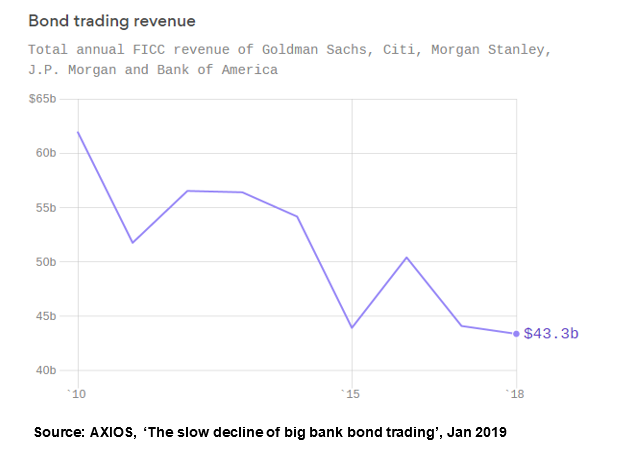

It’s not a coincidence that the fixed income trading operations of large global banks have been shrinking since 2009. They used to generate lots of profit from this activity but can no longer do so. These headlines give a sense of how large and pervasive these ongoing structural changes to the banking sector are:

“Goldman Sachs Group Inc. is considering plans to reduce the capital dedicated to its core trading business within the fixed-income group, a nod from the bank’s new chief that the business may not be as lucrative as in its glory days.”

– Bloomberg News, February 2019

“A recent survey by Coalition, a business intelligence provider, found that headcount in trading among the top global investment banks has been reduced by almost 20% since 2010 and 2015. Traders in fixed income appear to have suffered most, as poor annual revenues and increased regulatory costs have pressured investment banks to cut costs.”

– The Trade, September 2019

“Revenue from the once lucrative fixed-income trading business has fallen sharply in recent years and analysts say it will never recover to its peak levels.

… the regulatory regime that has been put in place since the 2007-8 crisis has brought major changes to how banks do business. Tougher capital requirements have significantly eroded profit in business areas such as FICC and forced executives to make tough decisions on capital deployment.

It’s no surprise then that banks are reacting to the new environment by cutting back, shedding staff and redirecting capital to other business lines.”

– MarketWatch, June 2014

“Bond traders have long defined Wall Street’s swagger and, in good years, generated a large share of its profits. Now, though, an upheaval is taking place in the bond business that is wiping out billions in profits and thousands of jobs.

Revenue from fixed-income trading among the top dozen global banks has already dropped from its height of $190 billion in 2009 to $105 billion last year, according to Keith Horowitz, who researches large banks for Citigroup.”

– New York Times, July 2012

The significant decline in fixed income revenues of banks over this period highlights just how profitable this opportunity used to be for the banks and now that same opportunity set is available other investors.

One such group of investors who have been taking advantage of this for many years are hedge funds. While they continue to do so, they are also negatively affected by the same bank balance sheet constraints that increased the opportunity set for them in the first place.

This is because most fixed income hedge fund strategies rely heavily on leverage, and that leverage comes from the same bank balance sheets that are now severely restricted and is therefore now more expensive and not as readily available. It’s not a coincidence that levered hedge fund assets under management have declined over the past 10 years.

A 2018 research report from the US central bank covered this theme:

“Since the 2007-09 financial crisis, the prices of closely related assets have shown persistent deviations – so-called basis spreads. Because such disparities create apparent profit opportunities, the question arises of why they are not arbitraged away.

In a recent Staff Report, we argue that post-crisis changes to regulation and market structure have increased the costs to banks of participating in spread-narrowing trades, creating limits to arbitrage. In addition, although one might expect hedge funds to act as arbitrageurs, we find evidence that post-crisis regulation affects not only the targeted banks but also spills over to less regulated firms that rely on bank intermediation for their arbitrage strategies.”

The question, then, is why less regulated arbitrageurs such as hedge funds don’t substitute for banks’ lower arbitrage activity. Our hypothesis is that, to the extent that arbitrageurs rely on regulated institutions for funding, clearing, and execution services, even non-regulated arbitrageurs may be affected by post-crisis regulations.”

“In addition, although hedge funds would serve as natural alternative arbitrageurs, we document that funds reliant on leverage from a global systemically important bank suffer significant declines in assets and returns relative to unlevered funds.

In the post-crisis regulatory environment, regulated broker-dealers not only are more constrained to participate in arbitrage trades themselves but also are less able to provide funding to their clients participating in these trades. This way the constraints imposed on regulated entities can pass through to unregulated arbitrageurs that rely on broker-dealers for funding.”

– Federal Reserve Bank of New York, ‘Bank-Intermediated Arbitrage’, July 2018

Two additional factors relating to non-economic market participants have also contributed to the growing opportunity around market inefficiency:

- extreme central bank intervention in bond markets, motivated by policy objectives

- rapid growth of passive fixed income funds, whose objective is to track indices rather than pursue profit

Both these groups buy and sell bonds for reasons other than profit maximisation, which means their very large flows cause temporary demand-supply imbalances that create pricing inconsistencies between very similar securities.

These are precisely the kinds of market inefficiencies that bank trading desks used to capture but are no longer able to. Therefore, there are now more of these opportunities available and far less competition to access them.

All these factors combined have increased opportunities for investors with the right expertise and experience to profit from the pricing inefficiencies left in their wake.

How can investors profit from market inefficiency?

One way to profit is by selectively accumulating bonds that have become mispriced as a result of market inefficiency, which is how a conventional active fixed income portfolio might operate. The portfolio can profit when the mispricing corrects and meanwhile can earn the yield from holding those bonds.

While this approach does access market inefficiency as a return source, it will also have exposure to broader market directional factors, such as interest rate duration risk. In practice, these market directional factors often end up becoming the dominant driver of the portfolio’s returns and overwhelm the portion of returns coming directly from pricing inefficiencies.

An unconventional but cleaner way to profit from market inefficiency is by adopting a pure ‘relative value’ investment approach. Such an approach seeks to precisely isolate the specific mispricing that has been identified by explicitly stripping out unwanted market directional exposures.

Fixed income market inefficiency creates a vast and diverse range of mispricing opportunities that ‘relative value’ specialists can exploit in a way that is independent of whether bond yields are high or low, is unaffected by which way interest rates move and remains uncorrelated to broader market fluctuations.

More detail on pure ‘relative value’ investing is available here.