Stellar bond returns … what’s driving them?

2019 has so far been a stellar year for bond returns globally. Even a simple passive exposure to long dated bonds has delivered handsome profits that far exceed the average yield of those bonds.

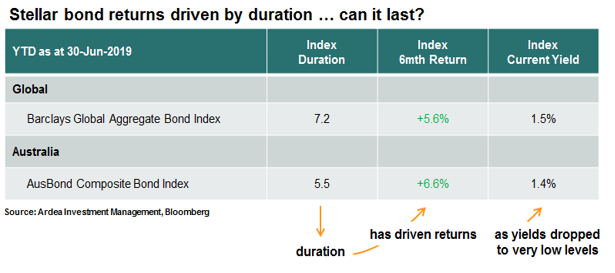

For example, the most widely follow global bond index (Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index) has delivered a 6 month return of USD 5.6% (almost 12% annualised!!!), despite the index yield starting the year at just 2% (i.e. the average yield of the bonds in the index).

Bond returns in Australia have been even more impressive. The most widely followed AU bond index (Bloomberg AusBond Composite Index) has returned 6.6% YTD and almost 10% over the past year. This index was yielding just 2.4% at the start of the year.

How can bonds deliver returns that are so much higher than their yields? The answer is duration.

Bond prices are constantly fluctuating just like stock prices. In the case of bonds, the price changes are driven by movements in various market interest rates, which are reflected in bond yields.

Duration is a measure of a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in bond yields (or interest rates more generally).

This sensitivity stems from the fact that a bond buyer makes a payment today (the bond price) in exchange for a series of future interest payments (the fixed rate of interest paid on that particular bond). At the time of purchase, the price of the bond will reflect the present value of that future stream of interest payments, which are fixed in advance.

However, the next day if the general level of interest rates (or bond yields) in the market rises, that fixed stream of interest payments is now below market value and therefore no longer as valuable. The bond would then need to be discounted to attract new buyers, and the bond price drops accordingly.

The longer dated the bond (i.e. longer duration), the more future interest payments need to be discounted and therefore the more pronounced this effect. Hence, longer duration bonds are more sensitive to interest rate movements.

Risk in this context is a two way street. If yields go up, bond prices go down and bonds incur capital losses. The opposite happens when yields go down.

This takes us back to the original question of bonds delivering returns higher than their yields.

The yield (or interest income) of a bond is only a part of its total return. The other part is the capital gain or loss stemming from the bond’s duration exposure. As bond yields have collapsed this year, duration exposure has delivered large capital gains.

An extreme example of this can be found in Japan. The Bloomberg Barclays Japan Govt. Bond Index has delivered a YTD return of 2.3%, even though the index yield started the year at just 0.09%.

This index has a duration of 9.9 years, which roughly means every 1% change in yields causes a 9.9% capital gain or loss. So, as the index yield declined by 0.17% this year (from 0.09% to the current level of -0.08%), the duration exposure created a capital gain of approx. 1.7% (i.e. 0.17% x 9.9), which accounts for the bulk of the YTD return. 1

This same dynamic has played out across bond markets globally as duration exposure has been the dominant driver of this year’s stellar fixed income returns. Even pure passive duration based bond portfolios have delivered great results this year.

But what duration gives can also be taken away.

For example, last year the global bond index referenced earlier delivered a negative return of 1.2% for the year and experienced a 7 month drawdown of 5.3% as US interest rates and bond yields rose.

As we noted last month, what’s particularly unusual about this year’s strong bond performance is that it has been accompanied by a strong equity rally, leaving bond yields at record low levels just as equity markets reach new record highs.

However, the asymmetry of risk vs return that’s inescapable when bond yields get very low is what makes chasing bonds at record low yields (i.e. record high prices) very different to chasing stocks at high valuations. Stocks can keep on going up indefinitely, while bonds can’t.

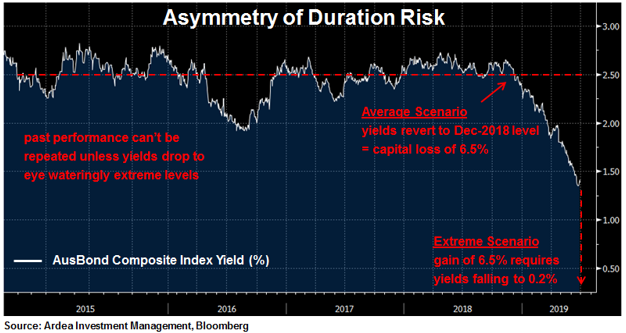

The chart below puts this asymmetry in context for AU bonds and brings to mind the ubiquitous but frequently ignored disclaimer that past performance is not indicative of future returns.

With yields already so low, the outlook for conventional duration focused bond portfolio returns is now heavily dependent on whether yields can keep going lower.

As the chart above highlights, the lower yields go, the more unfavorably asymmetric duration risk becomes. This means you need ever higher conviction in your directional view that yields will keep going lower, in order to counterbalance the asymmetry.

The problem is that directional calls on interest rates and bond yields are very hard to consistently get right. (we covered this here)

Of course yields could keep falling … one group of highly credentialed bond experts argues compellingly that yields will head lower as central banks cut interest rates in response to weakening economic growth.

But it’s far from certain how far that goes … another group of equally well qualified bond experts argues with high conviction that the economic outlook isn’t so bad, central banks won’t cut rates much and yields will rise.

Our view? Given all the variables, assumptions, feedback loops and subjective judgements involved we struggle to see how anyone can have high conviction about such a blunt directional market call. Remember it was only last year that the forecasting crowd was convinced rates would only go up, and now that same crowd is convinced of a dramatically opposing view.

These types of macro directional calls about the path of economic growth and how central banks will respond are inherently difficult (impossible?) to get right consistently. Even the bond kings and macro gods struggle.

Whichever camp you’re in, what’s clear is that the lower rates / buy duration view is a crowded one, as evidenced by record inflows to bond funds and the fact that interest rate markets already heavily pricing in aggressive central bank rate cuts.

Just because a position is crowded, doesn’t mean it’s wrong. However, history does tells us that when strong consensus expectations and crowded positions build up, the room for disappointment grows and a potentially violent re-pricing can follow if things don’t play out as expected.

We readily admit to having no competitive edge in predicting the future direction of interest rates, which is why we don’t take blunt duration risk in our portfolios.

Instead, we adopt a pure ‘relative value’ investment approach that is independent of the direction of rates and benefits from bond market volatility, irrespective of which way bond yields end up moving.

1 Note these calculations are approximations based on the average duration and yield of the index. A more precise calculation would need to account for the varying yield changes and duration exposures of the individual bonds in the index.