Reflation

The consensus is sure that inflation will remain lower for longer. Most remain sceptical that central banks will succeed in their mission to push it higher. Few think the risks of high inflation are even worth considering right now. All this brings to mind the Mark Twain quote:

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

The past decade’s experience of low inflation is being extrapolated far into the future and to such an extent that the ‘low-flation’ narrative has become entrenched. It seems we know for sure that high inflation won’t ever be a problem again, which is precisely what makes it a source of asymmetric risk and opportunity.

The events of recent months – a continuing global economic recovery, COVID vaccine progress, the unprecedented flood of co-ordinated monetary + fiscal policy stimulus – are taking place against a backdrop of ongoing global supply chain disruptions. This combination may in hindsight be recognised as the catalyst that finally undermined conviction in the low-flation narrative.

We don’t know if inflation will rise, fall or remain unchanged from here. Nobody does. What we do know is that unexpectedly higher inflation would disrupt the ‘lower for longer’ interest rates theme that has turbocharged asset prices everywhere, and in doing so could trigger a violent re-pricing across all asset classes.

Low inflation has been essential in giving central banks and governments the leeway to unleash extraordinary economic stimulus of a scale, speed and co-ordinated nature like never before. If the lagged effects of this stimulatory avalanche were to collide with a faster than expected economic recovery, what was meant to be a countercyclical policy safety net could snowball into a highly pro-cyclical and inflationary force. By that time policymakers will be stuck in an unprecedented stimulus cycle that cannot be reversed without causing huge disruptions.

That is of course just one scenario. On the other hand, the ‘lower for longer’ inflation and rates status quo could very well continue.

After a decade of trying and failing to stimulate inflation, if inflationary pressures do finally emerge, perhaps policymakers can somehow perfectly engineer just the right amount of inflation – higher but not too high – like getting just the right amount of sauce from the upturned bottle. Perhaps they can deftly navigate the delicate balance needed to maintain investors’ faith in the ‘lower for longer’ rates theme. Perhaps they can sustain the intersubjective belief that they have it all under control. Or perhaps not.

Either way, the narrow debate about whether inflation will rise or not misses the bigger picture risks and opportunities for multi-asset portfolios.

Often, when the consensus has been skewed in one direction for a long time and been correct, a powerful reinforcement of recency bias causes the prevailing narratives to become psychologically entrenched. Eventually this creates a favourably asymmetric opportunity for strategies that profit from opposing narratives, meaning they start to offer disproportionate upside relative to downside.

Applying this to the inflation outlook, it is not widely appreciated that pro-inflation strategies do not actually need higher inflation in order to profit. All they need is for the consensus to start questioning the entrenched ‘low-flation’ narrative. This would be the catalyst for at least some inflation risk premium being priced back into markets, from the current starting point of zero.

Even a modest shift in the inflation narrative, a modest rebuild of inflation risk premia, could trigger a rush to rebalance accumulated underweight inflation positions that have built up over many years. This would cause a demand spike for inflation linked assets that would be disproportionately large relative to their modest supply, in turn triggering outsized price reactions in niche segments like inflation linked bonds.

Thus, we have the makings of a favourably asymmetric opportunity to profit from an inflationary scenario. A scenario that would be damaging to multi-asset investment portfolios, which appear to be diversified, but in reality, hold lots of investments that would incur correlated losses if the ‘lower for longer’ inflation and rates status quo is disrupted.

Related to this, a rebuild of inflation risk premia would force the market pricing of interest rate volatility higher, from current record low levels. Inflation increases the tail risk volatility of government bonds, which therefore increases the volatility of multi-asset portfolios that combine bonds and equities. At the same time, it has never been cheaper to implement strategies that would profit from higher interest rate volatility. Another favourably asymmetric opportunity.

In this article we explore the following topics:

- the entrenched ‘low-flation’ consensus

- whether fiscal stimulus could be the inflation game changer

- inflation regime shifts and the possible catalysts for much higher inflation

- the interplay between ‘low-flation’ narrative and the ‘lower for longer’ interest rates theme

- why central bank credibility is key to whether we end up in a good or bad inflation scenario

- the asymmetric risks and opportunities created by inflation

The entrenched ‘low-flation’ consensus

The consensus view from the economic forecasting community, and from most investors, is still highly skewed to the ‘low-flation’ narrative (i.e. a prolonged period of low inflation), as it has been for a long time now. In fact, the inability of central banks to raise inflation over the past decade has been one of the most confounding developments for conventional economic analysis.

Economic orthodoxy suggests that stronger economic growth and rising inflation generally go hand in hand, but despite the long period of global economic recovery since the 2008 financial crisis, persistently low inflation has been a dominant feature of most western economies.

Possible explanations range from globalisation and technological change, to demographics, changing labour market dynamics and a structural decline in energy prices. Whatever the reason, the low-flation narrative has become entrenched enough to inspire magazine covers like the one below.

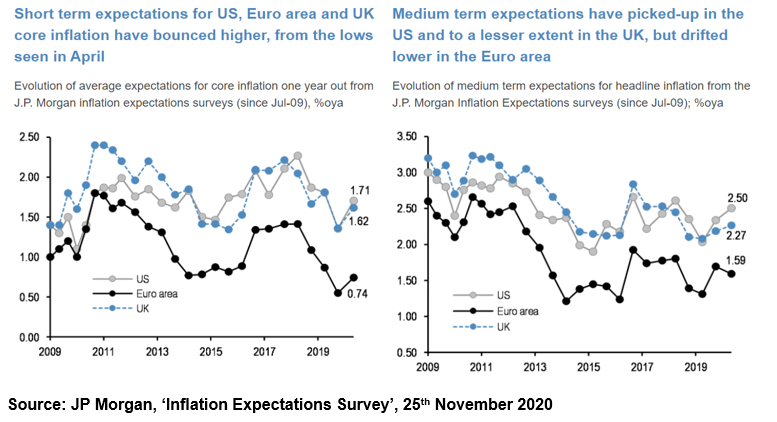

As JP Morgan’s latest survey shows, inflation expectations fell to near decade lows during the Q1 2020 COVID turmoil and have only rebounded modestly since then.

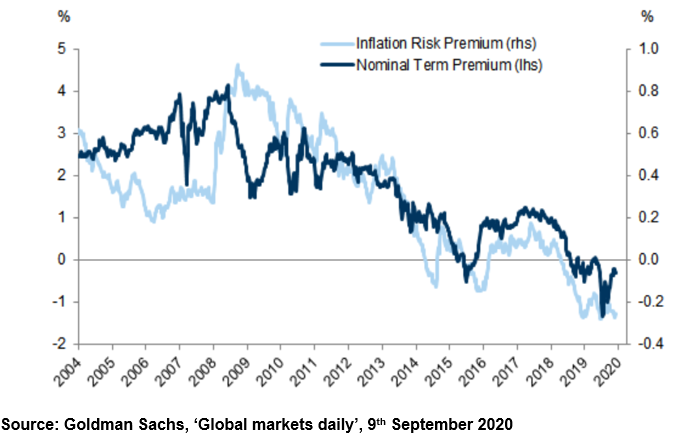

Other indicators of inflation expectations also a show a strongly entrenched low-flation consensus. For example, it manifests in how little inflation risk premium is reflected in the prices of assets that would be negatively impacted by (unexpectedly) higher inflation. The most obvious case being long duration government bonds because, niche use cases aside, no rational investor would own a 30 year government bond at zero (or indeed negative) yields, if they had any concern about rising inflation.

Getting a bit technical, we can estimate inflation risk premia by comparing the market pricing of securities in regular vs. inflation linked government bond markets. (a primer on inflation linked bonds is available here)

First, a caveat that these types of measures are inherently subjective estimates because 1) they are inferred from a pricing model, rather than being directly observable, 2) it’s difficult to disentangle all the different risk / return drivers that are embedded in the market price of any security and 3) the underlying market price inputs are somewhat ‘polluted’ by things like liquidity effects and temporary market inefficiencies. Nonetheless, as long as they are calculated in a consistent way over time, they can still give a sense of how inflation risk premia have evolved.

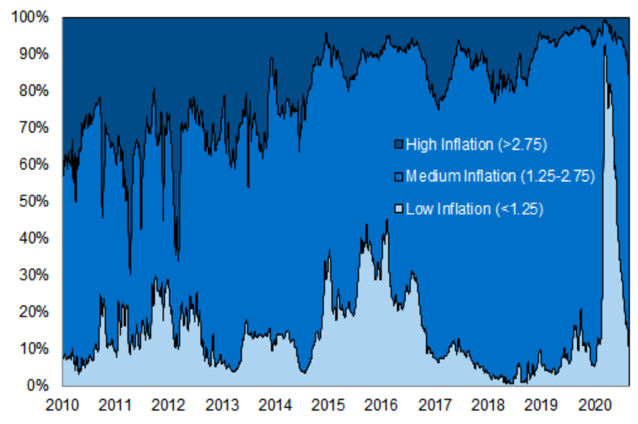

The first chart below shows the probability distribution of future US inflation scenarios, as implied by the actual market prices of inflation options. It clearly shows the skew towards low and modest inflation scenarios becoming more pronounced over time, while the probability assigned to high inflation scenarios has collapsed. Interpreted another way, inflation option buyers have become less willing to pay for options that profit in high inflation scenarios, while option sellers are happy to sell these options because they see little chance of the high inflation scenarios ever materialising.

The second chart shows another measure of inflation risk premium, this time based on the pricing of 10 year European government bonds. This shows an even more extreme dynamic, whereby the implied inflation risk premium has actually gone negative.

In assessing this type of data we draw a distinction between compensation for baseline expected outcomes vs. an additional risk premium to compensate for unexpected scenarios.

For example, when faced with a highly asymmetric risk vs. return profile, as one inherently is when buying long duration bonds at ultra-low yields, compensation for the unexpected but potentially very negative scenarios becomes more important. The unexpected higher inflation scenario would be less damaging if those bonds very giving you a nice yield cushion to hold them but in today’s environment that yield cushion is threadbare. (details here)

Accordingly, niche use cases aside, it only makes sense to own long duration bonds at near zero yields if you are so convinced of your baseline low-flation expectation that you pretty much dismiss the possibility of high inflation scenarios altogether. Therefore, one interpretation of very low (indeed even negative) inflation risk premia is that current market pricing of inflation sensitive securities has become overly skewed to the low-flation scenario, at the expense of severely under-pricing the probability of other possible scenarios. Current market pricing gives little allowance for the possibility that future inflation turns out to be much higher than what is currently expected.

This brings us back to the initial proposition that the low-flation consensus is well and truly entrenched. As much as anything else, perhaps this is just driven by the well-known behavioural bias to becoming overly anchored to present conditions / recent history, at the expense of considering a wider range of possibilities.

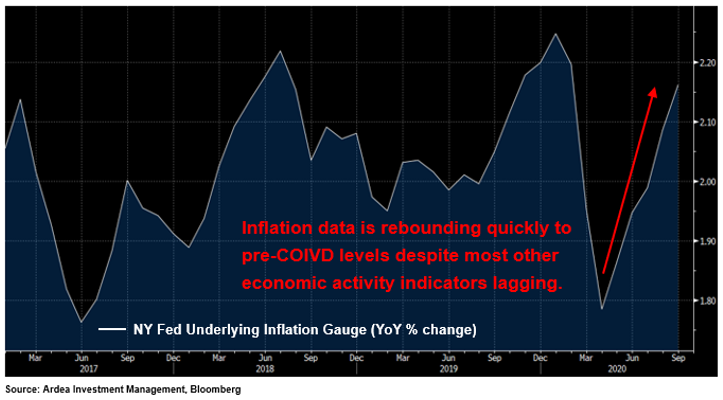

While most focus on the fact that inflation is low, we can get a useful perspective by applying the ‘inversion’ mental model popularised by the lesser known Berkshire billionaire, Charlie Munger. Rather than ask why inflation is low, it may be more useful to ask why inflation isn’t even lower in the face of such severe COVID induced economic disruptions. Given the strong disinflationary forces that were already in place for years before COVID hit, isn’t it surprising that inflation isn’t a lot lower?

In fact, not only hasn’t inflation fallen as much as might be expected, by some measures it is rebounding much faster than other economic activity indicators. For example, the New York Federal Reserve’s Underlying Inflation Gauge, which captures a broader range of prices than the narrow Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket, has already rebounded back to pre-COVID levels, even though US employment data remains depressed.

Extending this inverted line of thinking, there is a growing minority now pointing to this resilience of inflation as a warning sign of the future upside inflation risks that are building.

Could fiscal stimulus be the inflation game changer?

It must be acknowledged that recent history remains supportive of the low-flation consensus. So far, officially reported inflation statistics in most developed economies have remained consistently below central bank target levels and the big challenge has been to stimulate rather than suppress inflation.

With monetary policy historically being the tool of choice for stimulating inflation, some posit that it is fiscal stimulus which will be the game changer.

Back in our December 2019 market commentary, we noted the following:

“We now see more concern about the negative side effects of ultra-low interest rates and a growing consensus that when interest rates are already very low, the marginal benefit of further of monetary stimulus reduces, while the costs increase. (details here)

… The obvious alternative to stretched monetary tools is fiscal policy, which Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe has been vocal about. Commenting on a research report he oversaw, which assessed the efficacy on unconventional monetary policy tools such as negative rates and quantitative easing, he noted:

‘One key lesson is that the tools are most effective when used together with a broader set of policies, like fiscal and prudential measures.’

Dr Lowe’s remarks amplify his recent warning that monetary policy can only do so much and his calls for the Coalition government to inject more infrastructure spending and structural economic reforms to boost the sluggish economy.”

– Australian Financial Review, ‘QE most effective with broader fiscal policies’, Oct 2019

Fast forward to today and fiscal stimulus of epic proportions has been unleashed globally, which is a theme we discussed in detail here.

“Global fiscal frenzy is real & big: $10tn of announced fiscal stimulus in 2020 now greater than $8tn of monetary stimulus; fiscal is more powerful direct stimulus for economy than monetary policy.”

– Bank of America, ‘The Flow Show’, 4th June 2020

“The COVID-19 crisis has devastated people’s lives, jobs, and businesses. Governments have taken forceful measures to cushion the blow, totaling a staggering $12 trillion globally. These lifelines have saved lives and livelihoods. But they are costly and, together with sharp falls in tax revenues owing to the recession, they have pushed global public debt to an all-time high of close to 100 percent of GDP.”

– IMF, ‘Fiscal Policy for an Unprecedented Crisis’, 14th October 2020

2020 has seen global fiscal stimulus of a magnitude that is unprecedented outside of wartime. We did not see this in response to the 2008 crisis. In fact, from 2010 onward the focus was more on fiscal austerity and balanced budgets in most western countries. However, the political narrative has now shifted in favour of aggressive spending to counterbalance government imposed restrictions on economic activity. Governments are erring on the side of doing too much rather than too little in trying to mitigate worst case economic outcomes.

While the transmission mechanism from fiscal stimulus to inflation is complex and unclear, it is notable that much of the stimulus in many countries is via direct money transfers from governments to households. Compared to other methods of fiscal stimulus, such as infrastructure spending, direct cash transfers have a higher propensity to be spent and therefore be more inflationary.

“Hong Kong permanent residents aged 18 and above will each receive a cash handout of HK$10,000 (US$1,200) in a HK$120 billion (US$15 billion) relief deal rolled out by the government to ease the burden on individuals and companies, while saving jobs. … Much touted but seldom tried, economists have long seen helicopter money as the most radical tool that central bankers could deploy to fight a weak economy…”

– Financial Times, ‘Helicopter money is here’, 26th February 2020

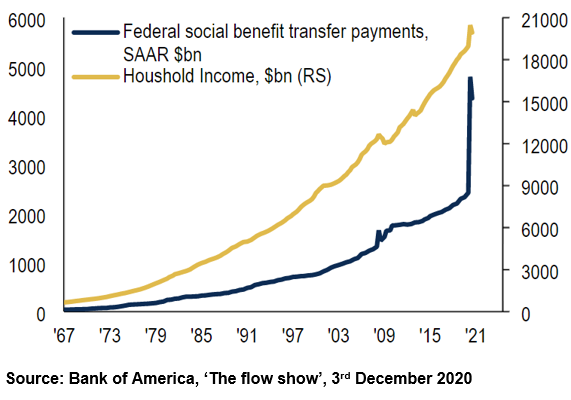

The chart below provides some perspective on the sheer size of the c. $2tn of benefit payments made by the US government directly to US households since COVID hit.

With most fiscal stimulus commentary focusing on the risks of unsustainable government debt levels, there has been little on the implications for inflation. While conventional economic theory suggests inflation is largely a monetary phenomenon, and has less to do with fiscal policy, that same conventional thinking has failed to explain why inflation has remained so stubbornly low for the past decade. Newer schools of thought suggest the relationships between monetary policy, fiscal policy and inflation are more complex than previously thought. (e.g. How fiscal policy drives inflation.)

A research note from Morgan Stanley brought these two schools of thought together, arguing that what’s really different about the current environment is the unprecedented combination of large scale monetary and fiscal stimulus being engaged at the same time. They refer to the US case specifically, but similar dynamics are playing out globally.

“While we are likely to experience big imbalances in the real economy for several more quarters, if not years, the most powerful leading indicator for inflation has already shown its hand—money supply, or M2. As Milton Friedman famously said 50 years ago, ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’ It’s fair to say we have never observed money supply growth as high as it is today.

Of course, money supply also grew rapidly after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and we never saw inflation appear in a meaningful way. This fact has emboldened the view that the Fed can print money at whatever rate they want, and it won’t lead to inflation, at least not enough inflation to cause nominal and real long term interest rates to rise much from here. Given the historically low levels of rates and crowdedness of long duration assets, that may prove to be a dangerous assumption.

We’ve argued for the past several months that the policy response to this crisis has been very different than what was used during the GFC. On the monetary front, the Fed reacted much more swiftly and aggressively with its immediate response and direct intervention in credit markets. In short, they went all-in from the beginning showing no hesitation to do whatever it takes to support markets and the economy. Part of that aggressiveness was also likely attributable to the fact that we didn’t get any meaningful inflation after $4 trillion in Quantitative Easing following the GFC. However, it’s the fiscal response that’s really different this time.

First, the government has been sending money directly to both consumers and small businesses as a means of supporting the economy during the lock down and reopening—aka “helicopter money.” Second, they have directly intervened in the lending markets by making loans via the Paycheck Protection and Main Street Lending Programs. Finally, and perhaps most importantly for the inflation call, is the decision by Congress to guarantee loans made by commercial banks and to offer mortgage and other liability (rent) forbearance via the CARES Act.

… Congress is now in the driver’s seat when it comes to the money supply with its fiscal programs and as Milton Friedman also famously said, ‘Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.’ This is potentially more inflationary than appreciated which means back end rates can rise. Very few portfolios are prepared for such an outcome. Such shifts can happen quickly when they are so unexpected …”

– Morgan Stanley, US Equity Strategy, 13th August 2020

Related to the theme of co-ordinated fiscal + monetary policy action, it is well recognised that letting inflation ‘run hot’ for a while can be a tempting policy choice for governments struggling to get their elevated debt to GDP ratios back under control. This is the kind of convenient ‘solution’ that is tempting for politicians but comes with significant risk of unintended consequences, and once unleashed can be hard to control.

“… there’s another way that the government can shrink the mountain of debt weighing down the U.S. economy: inflation. Because most interest payments are fixed in nominal terms, inflation makes existing debt less important in real terms. Raising the long-term inflation target from the current 2% to a still-modest 4% would substantially increase the rate at which debt effectively vanishes.

The U.S. has used inflation this way before. Economists Joshua Aizenman and Nancy Marion wrote – ‘The average inflation rate over this period [from 1946 to 1955] was 4.2%…inflation reduced the 1946 [federal] debt/GDP ratio by almost 40% within a decade.’

A decade of 4% inflation today would do the same for total debt, not just government debt.”

– Bloomberg, ‘Inflation is the way to pay off Coronavirus debt’, 7th May 2020

“The truth is that governments have an inherent bias towards inflation, especially under adverse conditions such as wars and revolutions. The Covid-19 lockdown is another such condition. Tomorrow’s inflation will alleviate some of today’s financial problems: debt levels will come down and inequalities of wealth will be mitigated. Once excessive debt has been inflated away, interest rates can return to normal. When that happens, homes should be more affordable and returns on savings will rise.

But the evils of inflation should not be overlooked. Economies do not function well when everyone is scrambling to keep pace with soaring prices. Inflations produce their own distributional pain. Workers whose incomes rise with inflation do better than retirees. Debtors will thrive at the expense of creditors. Profiteers arise, along with populists who feed on social discontents.”

– Financial Times, ‘Can governments afford the debts they are piling up?’, 3rd May 2020

Inflation regime shifts

History shows that once a prevailing inflation narrative becomes entrenched – as ‘low inflation forever’ has become over the past decade – it takes more than just a single catalyst to change it.

“Inflation regime shifts tend to have several consecutive or simultaneous drivers. They tend not to have a single explanation such as ‘high debts levels’ or ‘money printing’. They often reflect broader contemporaneous social, political and economic dynamics (e.g. social upheavals, demographics, wars and their aftermath). The common drivers of inflation regime shifts are, therefore, a combination of: supply-side constraints or reforms, FX shocks, fiscal issues, institutional reforms, event-driven shifts in expectations, food/commodity shocks and demand shocks exogenous to all previous categories.

… In the late 1960s / early 1970s social pressures led to higher fiscal spending and increased labour bargaining power. A series of country-specific shocks also facilitated the inflationary push, but policymakers were generally reluctant to tighten policy enough, allowing a permanent shift in inflation. The 1970s oil shock reinforced the inflationary issues and it was only in the late 1970s/early 1980s that credible committed policy efforts could break the inflationary spiral.

– Deutsche Bank, Economics Research, 15th July 2020

Back in 2008, when the US Federal Reserve cut interest rates aggressively and began its first QE program, some feared that rampant inflation and debasement of fiat currencies would be the end result. Yet, despite hundreds of interest rate cuts and many QE programs being implemented globally since then, traditional measures of consumer price inflation have mostly fallen. The risk of deflation rather than inflation has become the main concern … but could this time be different?

We cannot reliably predict whether inflation will increase from here or not, given the complex web of variables and feedback loops involved. However, we can point to multiple catalysts, which in combination could be enough to trigger an inflation regime shift.

1.Monetary stimulus is ‘all in’

The sheer scale and speed of post-COVID monetary policy stimulus is far greater than what we saw in response to the 2008 crisis. Central banks globally are now ‘all in’ on monetary stimulus, with the largest among them explicitly stating they will do ‘whatever it takes’ to mitigate near-term downside risks to economies and financial market stability.

Per Bank of America estimates, the big 5 central banks (ex-China) cumulatively bought c. $13 trillion of financial assets via QE over the entire 11 year period from the Lehman default in 2008 to the end of 2019. They have bought c. $8 trillion in just the past nine months since COVID hit, on top of which there have been 190 interest rate cuts from all central banks over this period.

The scale aside, they are also pushing further into uncharted territory by scrapping existing self-imposed limits on the scope of their asset purchases. For example, the FED has committed to unlimited buying of corporate debt and the ECB has scrapped limits on the breadth of EU assets it can buy. It’s unclear where are all this ends.

2.Fiscal stimulus is ‘all in’

This is discussed in the previous section – ‘Could fiscal stimulus be the inflation game changer?’.

3.Policy co-ordination is ‘all in’

Compared to the 2008 crisis response, we are now seeing more co-ordination between fiscal and monetary policies in most countries, which is notable because some argue that one of the main reasons policymakers failed to stimulate inflation over the past decade was precisely due to a lack of policy co-ordination. In fact, in some ways the fiscal policy focus on balanced budgets was working in the opposite direction to monetary policy in many countries.

Now we have policy co-ordination going to other extreme, for example with central bankers being more vocal about the need for fiscal policy to step up, the talk of debt monetisation (details here), the appointment of former US central bank governor Janet Yellen as the new US treasury secretary etc.

Commenting on this unprecedented fiscal + monetary co-ordination (specifically in the US), Bank of America noted:

“… nothing matters but liquidity … GDP loss of $10tn & US claims 53mn numbed by $21tn policy stimulus, $2bn per hour central bank asset purchases … Deficits soaring: U.S. federal budget deficit @ 25% of GDP if Phase IV fiscal stimulus >$1tn, highest since 1943 WWII peak of 27.5% (Chart 4). Fed printing: central bank stimulus $9tn in 2020; global liquidity supernova continues until a. melt-up on Wall Street causes trickle-down into Main Street wages, and/or b. unemployment <5% & CPI >2%.”

– Bank of America, The Flow Show, 6th August 2020

4.Policy time lags

Unlike the gradual process of decline we see for most recessions, this one happened suddenly. For example, the US swung from record low unemployment to off-the-charts record high jobless claims in just a few weeks. Therefore, it is entirely possible that the recovery on the other side is just as sudden, particularly given the speed and scale of the policy stimulus response, together with faster than expected COVID vaccine progress.

We know that monetary and fiscal stimulus have time lags before their full economic effects are felt. Therefore, in a quick economic recovery scenario this avalanche of policy stimulus will flip from being a countercyclical safety net to becoming highly pro-cyclical. By that time policymakers will be stuck in an unprecedented stimulus cycle that they can’t reverse without causing huge disruptions.

For example, recognising that overleveraged economies are too fragile to stomach rapid interest rate hikes and perhaps also hindered by recency bias – when you’ve spent a decade trying and failing stimulate inflation, it’s hard to quickly shift your mindset back to curbing it – central banks will necessarily be slow to raise rates, even as they see inflationary pressures building.

One historical analogue is post-war recovery periods, which show that the natural demand recovery after a period of extreme restrictions, combined with massive fiscal and monetary stimulus, created inflation in the range of 5-10% or even higher.

5.Nothing is off the table

2020 has seen previously fringe policy ideas getting serious mainstream attention, most notable of which is Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Without delving into all the complexities, the basic idea of MMT is that a government can raise unlimited amounts of debt in its own currency and then simply print more money (via the central bank) to pay off those debts.

It’s an idea from the 1940’s that now has high profile advocates in places like the US Democratic Party, even though prominent mainstream economists and policymakers dismiss it as dangerously experimental.

The binding constraint on MMT, as its own proponents explicitly acknowledge, is inflation. Central banks printing money to fund government expenditure can quickly become dangerously inflationary if central banks lose credibility on their inflation control narrative. MMT proponents offer various ideas to manage the inflation risk (e.g. tax increases, enforced savings policies) but none have been tested.

The big risk is that recency bias (i.e. the recent experience of low inflation) emboldens politicians to aggressively push for policy approaches like MMT in the (mistaken) belief that inflation risk is too remote to worry about.

6.Supply side disruptions

This is the wildcard. While the consensus is still focused on COVID induced demand disruptions, it is the supply side impacts that may turn out to be more important.

Suppliers of goods and services were forced to close, not because of weak consumer demand, but because of government orders. Many of them will be slow to re-open (if they re-open at all) because there can be substantial costs involved in shutting down and then restarting production. Additionally, COVID has disrupted global supply chains via border restrictions, worker mobility constraints, rising aversion to global trade etc.

As Ken Rogoff points out, the supply side is what makes the current recession different:

“But policymakers and altogether too many economic commentators fail to grasp how the supply component may make the next global recession unlike the last two. In contrast to recessions driven mainly by a demand shortfall, the challenge posed by a supply-side driven downturn is that it can result in sharp declines in production and widespread bottlenecks. In that case, generalised shortages – something that some countries have not seen since the gas queues of 1970s – could ultimately push inflation up, not down.

Admittedly, the initial conditions for containing generalised inflation today are extraordinarily favourable. But, given that four decades of globalisation has almost certainly been the main factor underlying low inflation, a sustained retreat behind national borders, owing to a Covid-19 pandemic (or even lasting fear of pandemic), on top of rising trade frictions, is a recipe for the return of upward price pressures. In this scenario, rising inflation could prop up interest rates and challenge both monetary and fiscal policymakers.”

– Guardian, ‘A coronavirus recession could be supply-side with a 1970s flavour’, 3rd March 2020

Given inflation ultimately comes from aggregate spending exceeding aggregate production capacity, COVID related supply chain disruptions, together with an acceleration of trends such as de-globalisation and populist focus on lifting wages, the potential cost push impact on inflation seems underappreciated.

“… while we may be in the midst of a reduction in what mainstream economists call ‘aggregate demand,’ we are also seeing a significant supply-side shock. The former typically has deflationary tendencies, while the latter causes price inflation. A supply shock is simply an event which impedes the ability for supply chains, or the structure of production, to maintain the allocation of capital and labor so that they can produce a given level of output.

What began as a reduced supply of imports to the US from China has developed into an even deeper supply-side issue, with government-enforced shutdowns for “nonessential” businesses, rising domestic unemployment, and reduced production as a record 6.6 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits in the last week of March.”

– Mises Institute, ‘This isn’t your usual demand-shock recession’, 15th April 2020

“To summarise our arguments: First, we believe that the Great Covid-19 Recession (GCR) will be a sharper but shorter recession than the global financial crisis (GFC). Second, the public health crisis has galvanised policy-makers to respond swiftly. The timing, scale and coordinated policy easing will lift us out of the low-growth, low-inflation loop. Third, the economic shock is driving an even deeper wedge between low- and high-income workers. We therefore expect increased scrutiny of trade, tech and titans, given their role in driving the wage share of GDP lower and widening the income divide. Disturbing this trio will also mean disrupting the key structural disinflationary forces of the past 30 years.

… Addressing the pushback from investors: Just as we thought, the consensus remains firmly anchored in the disinflation camp. Most of our discussions were centred on the pace of the cyclical recovery and whether policy easing will be effective. While investors heard us out on the disruption to tech, trade and titans, they are generally downplaying its impact on inflation and believe that weaker demand conditions will persist, keeping inflation at relatively low levels.”

– Morgan Stanley, Global Macro Briefing, 21st May 2020

Linking all these potential catalysts to the current backdrop, it’s not hard to envisage the makings of an inflationary regime shift.

For example, imagine a scenario in which the nascent rebound in global economic activity, turbocharged by vaccine progress, collides with the fastest money supply growth on record and the lagged effects of unprecedented monetary + fiscal stimulus flipping from their intended anti-cyclical objective to becoming highly pro-cyclical on the demand side. Added to this, we can have cost push pressures from accelerating structural changes like de-globalisation and populist political pressure to raise wages for those at the bottom of the income spectrum, while COVID induced supply side disruptions continue to hold back production capacity.

Lower for longer … no longer?

If inflationary pressures do indeed accelerate this time, we will see important thematic shifts across the global investing landscape.

For the past decade, global financial markets have been dominated by the expectation for a prolonged period of ultra-low interest rates – the so-called ‘lower for longer’ interest rates theme. This theme has been highly supportive of financial asset prices and could not have persisted without the entrenched expectation that inflation would also remain low for a long time – the ‘low-flation’ narrative.

Ultra-low interest rates optically push up asset prices via discount rate effects, but more importantly have catalysed a wall of capital to progressively move up the risk spectrum as investors sought to maintain returns in the face of falling interest rates … the so called ‘reach for yield’.

In fixed income this manifested as capital rotating out of cash deposits and government bonds into progressively riskier credit securities. More broadly, capital has poured into everything from equities to emerging markets, property, leveraged ETFs etc. … basically anything that offered a return above zero.

As decision making became increasingly skewed by the collapsing returns available from cash and other lower risk assets, the desperate search for returns trumped considerations of the risks being taken to earn those returns. Thus, with cash returning nothing, pretty much anything else looked good and therefore financial asset prices rose, while risk premia fell.

Intimately linked to all of this has been the ‘good inflation’ narrative. This is where rising inflation is viewed as a positive sign of economic growth, but still moderate enough as to not trigger a more restrictive monetary policy stance. This is a finely balanced scenario that remains supportive of financial asset prices as it allows the ‘lower for longer’ theme to persist.

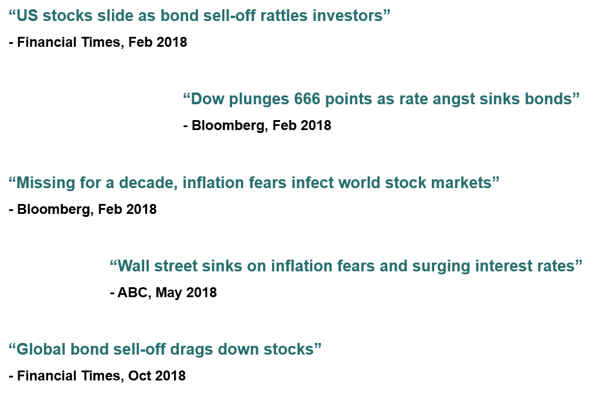

However, if inflation were to accelerate beyond a moderate level, we risk transitioning to a ‘bad inflation’ narrative. This is where the possibility of inflation materially overshooting central bank targets raises the fear of aggressive interest rate hikes, which in turn would undermine the ‘lower for longer’ narrative and its associated capital flows. This would be very disruptive for financial markets, as we got just a small taste of in 2018.

Recall in 2018, it was the fear of rising US inflation triggering aggressive rate hikes that eventually caused turmoil across global financial markets. It was not a coincidence that the S&P 500 fell 19.6% from October 3rd, 2018 into year-end – at the time its largest drawdown since the 2008 financial crisis – after the FED made the following comments:

“The really extremely accommodative low interest rates that we needed when the economy was quite weak, we don’t need those anymore. They’re not appropriate anymore. Interest rates are still accommodative, but we’re gradually moving to a place where they will be neutral. We may go past neutral, but we’re a long way from neutral at this point, probably.”

– US Federal Reserve Chairman Powell, October 3rd, 2018

In reviewing that period, we noted the following regarding the impact on capital flows of rising rates and withdrawal of QE:

“We’ve highlighted previously that the combination of abnormally low interest rates and QE was akin to the bar tab that had kept the markets party going in the post financial crisis era and that it had clouded investor judgement on risk and asset pricing … near zero interest rates can make any asset look attractive.

And so it was that 2018 goes down as the year when the central bank bar tab finally ran out, causing a more sober evaluation of asset prices to re-assert itself. It’s not only the fear of a FED induced recession that hurt asset prices this year. Equally important is the fact that investors now actually get paid something to hold cash.

For most of the post financial crisis era the decision to chase growth in equities or yield in credit was heavily skewed by the high opportunity cost of keeping capital in cash at zero rates. With cash returning nothing, pretty much anything else looked good.

But over the past 18 months, as cash rates have risen materially, while expected returns from other asset classes have also declined, that opportunity cost effect weakened, resulting in a reversal of those yield seeking capital flows.

These dynamics are central to understanding why equity and credit markets had such a bad year in 2018, despite a backdrop of economic growth, corporate earnings and low default rates that were all positive.”

– Ardea Investment Management, 15th January 2019 (details here)

As we saw in 2018, it doesn’t take much for the ‘bad inflation’ narrative to take hold and that risk is currently asymmetric because markets are already fully priced for the ‘good inflation’ scenario to continue. It is ironic that very thing that policymakers have been seeking – inflation – may well end up being the catalyst for a violent sell-off in financial markets.

Looking forward, this good vs bad inflation tension is relevant from an overall portfolio construction perspective because all asset prices have become so correlated around the ‘lower for longer’ theme. Stretched valuations everywhere from equities to bonds to property have been justified to a large extent by the expectation that ultra-low interest rates will be with us for a long time.

As Morgan Stanley pointed out just before COVID hit:

“At present, we think investors are either sceptical of a sustained rise of G3 inflation, or would welcome it, a sign of better growth and returning normality. Our economic forecasts also have inflation rising in 2020, but central banks effectively embracing that rise with no change in policy.

But it is not that long ago, in 2018, when markets viewed a rise in inflation as more problematic. In 2019, every asset has rallied. But in 2018, almost every asset declined, and markets began to worry that excess capacity in the global economy was being used up. Inflation is a risk to our narrative that we need to watch.”

– Morgan Stanley, ‘Cross Asset Dispatches’, December 2019

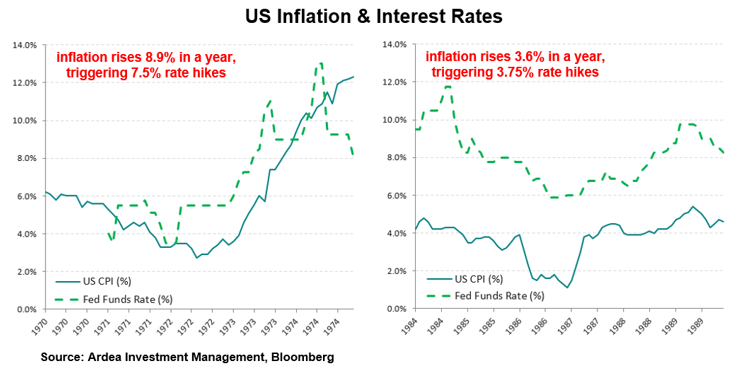

Because we are vulnerable to recency bias, it is easy to forget how quickly things can change. The charts below remind us that inflation regime shifts can happen quickly, as can interest rate changes.

The purpose of these charts is not to make a comparison between the inflation dynamics today vs. those historical periods – clearly the macroeconomic conditions, structural forces etc. are different. Rather, it is just to remind us how quickly narratives can change.

Central bank credibility

We do not know whether inflation will rise from here or not. We do know that if it does, central bank credibility will be the key determinant of whether we end up in a good or bad inflation scenario.

In a scenario where economic growth continues to improve and inflation rises, as long as consumers and financial market participants believe that central banks can maintain just the right level of inflation – higher but not too high – we will have a good inflation scenario, where inflation is seen as a desirable side effect of stronger economic growth.

However, if central bank credibility is doubted and the narrative shifts to concerns about runaway inflation, we will have a bad inflation scenario, where inflation is seen as an undesirable catalyst for rising interest rates.

We got just a small taste of a bad inflation scenario back in 2018, the result of which was a large bond market sell-off that spilled over into equities and other risk assets. That highly correlated sell-off wasn’t surprising given how all asset prices had become so dependent on the ‘lower for longer’ interest rates theme.

We now have central banks revising their policies to intentionally overshoot their inflation targets on the upside, in order to make up for past below-target inflation.

“… the Fed has revised its long-term monetary policy in a way that allows for more inflation. Previously, the central bank aimed to hit its 2% target regardless of how far or how long inflation had strayed from that objective in the past. Now the Fed wants inflation to average 2%, which means it will have to exceed 2% for a significant time to offset the chronic downside misses that have accumulated over the past decade.

Specifically, Fed officials have said that they won’t raise short-term interest rates until employment is at its maximum sustainable level, and inflation has reached 2% and is expected to go moderately higher for some time. This means they’re unlikely to respond to any inflation uptick until they expect it to be both persistent and sizable.”.

– Bloomberg, ‘Five reasons to worry about faster US inflation’, 3rd December 2020

Added to this, we have governments continuing to pile on more fiscal stimulus as the most convenient political narratives currently favour erring on the side of doing too much rather than too little in mitigating the COVID shock. And we know from the past decade’s experience that stimulus is hard to wind back once unleashed because financial markets have developed a Pavlovian conditioning to panic at the slightest sign of stimulus withdrawal.

Against this backdrop of central banks intent on running inflation ‘a bit hot’ and politicians simultaneously going all in on fiscal stimulus, the burden of proof on central bank credibility has increased.

In order to maintain faith in the ‘lower for longer’ interest rates theme that has been so favourable for assets prices everywhere, central banks need to maintain the intersubjective belief that they have it all under control, that they can engineer a modest inflation increase, without letting it run too far. As soon as a variant perception gains momentum, we risk spiralling into a bad inflation scenario.

“Ironically, the greater the deflationary concerns that policymakers must fight today, the greater the debt build up and the higher the inflationary risks are in the future.

The deflationary shock caused by the pandemic drives the need to expand balance sheets to support demand today, as seen in the latest US $1.0 trillion Phase 4 stimulus and the €750 billion pan-EU recovery fund. The resulting expanded balance sheets and vast money creation spurs debasement fears which, in turn, create a greater likelihood that at some time in the future, after economic activity has normalized, there will be incentives for central banks and governments to allow inflation to drift higher to reduce the accumulated debt burden.

Indeed, this has already been seen in recent FOMC minutes, as discussions of explicit outcome-based forward guidance raises the prospect for Fed-sanctioned overheating of the economy. Despite the longer-term nature of these risks, asset managers have real concerns today about persistent unanticipated shifts in inflation that can create large discrepancies between current expected real returns and actual realized returns.”

– Goldman Sachs, Commodity Research, 28th July 2020

How realistic is the goldilocks ‘higher but not too high’ inflation scenario? It is certainly possible, but given how hard it has been for central banks to stimulate inflation over the past decade, one could argue it is naïve to simply assume they can precisely calibrate policy to deliver inflation that’s high enough, with no risk of spiralling much higher. Yet, that goldilocks assumption is pretty much what’s reflected in current market pricing, given the lack of inflation risk premia evident across financial markets today. (details in the earlier section – ‘The entrenched ‘low-flation’ consensus’)

This leads to a further consideration relating to central bank credibility. When central banks aggressively intervene in bond markets, bond prices lose their information value. We have already seen this in Japan and are now seeing it across EU government bond markets.

When functioning normally, bond market pricing can act as a disciplinary check on the actions of central banks and governments. For example, if monetary policy is too loose and inflation risk is rising, or if government borrowing is becoming unsustainably high, bond markets will reflect this by pushing up the risk premia incorporated in bond prices, which would manifest as lower bond prices / higher bond yields. Aggressive central bank intervention dampens these pricing signals, which means inflationary pressures, unsustainable debt levels etc. can continue building up without any market based disciplinary check. It is therefore then left entirely up to central bankers and governments to control themselves.

How confident can we be that a small group of powerful policymakers with little real-world accountability, can walk the delicate balance between too much or too little policy stimulus? Of course the policymakers would like us to be highly confident in their abilities.

Back in 2015, BOJ governor Kuroda began a policy speech explaining the BOJ’s extreme monetary policy stance by invoking Peter Pan:

“I trust that many of you are familiar with the story of Peter Pan, in which it says, ‘the moment you doubt whether you can fly, you cease forever to be able to do it,’ …”

As monetary policy increasingly reaches its limits, the power of central banks becomes increasingly reliant on belief in their words, in their narratives, rather than the concrete positive impacts of their actions. ‘I believe I can fly’ might be confidence inspiring to some but sounds delusional to others.

A pre-COIVD paper co-authored by former US Federal Reserve vice chair Stanley Fischer argued that ‘unprecedented policy co-ordination’ will be needed to fight the next economic downturn. Recognising the risks of outright debt monetisation, the authors advocated a middle path of fiscal and monetary policy co-ordination that mitigates these risks. While that sounds good in theory, in practice it requires policymakers to manage an extremely delicate balance in engaging extraordinary stimulus measures, while still maintaining a credible narrative around inflation and budget deficit control.

Such narratives only hold as long as the majority thinks that the majority still believes in them. Once that belief is questioned, dramatic paradigm shifts can occur. Such shifts tend be subtle at the beginning and few notice the signs, but then they quickly gain momentum as confidence in the old narratives crumble and the variant perception becomes the new consensus.

Looking beyond the narrow ‘higher vs. lower’ inflation debate

We cannot reliably predict whether inflation is headed higher or not. In fact, given all the variables involved and the complexity of their interactions, we’d argue nobody can. Reinforcing this point, back in May Deutsche Bank published a post-COVID outlook in which one group of analysts made a compelling argument for inflation, immediately followed by another making an equally compelling case for deflation. The conclusion – nobody really knows.

“The case for inflation

As policymakers launch unprecedented stimulus packages, it seems the coronavirus will be inflationary. Add in the supply shock from retreating globalisation, the increase in labour’s bargaining power, as well as the need to reduce large debt burdens, and it means inflation is back on the agenda.

The case for deflation

With the deepest recession in generations taking hold, it is remarkable that many dismiss the deflationary consequences. Deleveraging will be a feature of the landscape for years to come, any fiscal boost will ultimately prove temporary, while any reverse in globalisation would take decades to feed through.”

– Deutsche Bank, Konzept ‘Life after COVID-19’, 13th May 2020

However, the narrow debate on higher vs. lower inflation misses the bigger picture risks and opportunities for multi-asset portfolios. A more useful approach is to understand the current consensus views and the extent to which they are already reflected in current market prices. We can then consider how the consensus might be challenged and what the resulting impact on future market prices might be.

Often, when the consensus has been skewed in one direction for a long time and been correct, the prevailing narratives become psychologically entrenched, as recency bias is powerfully reinforced. Eventually this creates a favourably asymmetric opportunity for strategies that profit from opposing narratives, meaning they start to offer disproportionate upside relative to downside.

We can certainly point to narratives that have become entrenched over the past decade – ‘low-flation’ and by extension, ‘lower for longer’ interest rates. We can also see the growing list of catalysts discussed earlier in this article, which could conspire to challenge these entrenched narratives. Finally, we can see how an inflation narrative shift could trigger a potentially violent disruption to the status quo pricing across pretty much all asset classes. This would cause substantial damage to multi-asset investment portfolios, which appear to be diversified, but in reality, hold lots of investments whose performance is reliant on the low inflation / low rates status quo continuing.

Additionally, we see two further thematics that could reinforce the asymmetric nature of the inflation related risks and opportunities:

- Having been entrenched in the low inflation narrative for so long, many large pools of institutional capital have materially down weighted (or even abandoned entirely) their strategic asset allocations to inflation linked assets.

- The supply of explicitly inflation linked assets has remained modest relative to the global investment universe. For example, inflation linked bonds only represent a small portion of the total fixed income universe.

Applying this to the inflation outlook, it is not widely appreciated that pro-inflation strategies do not actually need higher inflation in order to profit. All they need is for the consensus to start questioning the entrenched ‘low-flation’ narrative, which would be the catalyst for at least some inflation risk premium being priced back into markets, from the current starting point of zero.

Given these underlying thematics, even a modest shift in the inflation narrative, a modest rebuild of inflation risk premia, could trigger a rush to rebalance the accumulated underweight inflation positions that have built up over many years. This would cause an aggregate demand spike for inflation linked assets that is disproportionately large relative to their modest supply, in turn triggering an outsized price reaction in niche segments like inflation linked bonds.

As such, if we can look through short term performance volatility potential to think more about medium term portfolio construction and strategic asset allocation, inflation related strategies have the makings of a favourably asymmetric opportunity.

Related to this, a rebuild of inflation risk premia would force the market pricing of interest rate volatility higher, from current record low levels. Inflation increases the tail risk volatility of government bonds, which therefore increases the volatility of multi-asset portfolios that combine bonds and equities. At the same time, it has never been cheaper to implement strategies that would profit from higher interest rate volatility. Another favourably asymmetric opportunity.

This material has been prepared by Ardea Investment Management Pty Limited (Ardea IM) (ABN 50 132 902 722, AFSL 329 828). It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Any projections are based on assumptions which we believe are reasonable, but are subject to change and should not be relied upon. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Neither any particular rate of return nor capital invested are guaranteed.