Fiscal is the new black ( …until the bond vigilantes return )

In this article we explore the following topics:

- Why fiscal policy has been forced to take over from monetary policy

- How large the impending fiscal stimulus blitz will be

- The implications for government bond markets of so much new bond supply

- The potential end game scenario of central banks buying everything and monetising debt

- The longer term risks from all this policy stimulus

- The asymmetric profit potential from pure inflation exposure

- The implications of all this for multi-asset portfolio construction

Introduction

Unprecedented global fiscal stimulus. Extreme monetary policy experiments. Yields at multi-century lows. Government bond markets are now at the precipice of a paradigm shift.

In combination, these factors fundamentally change the risk vs. reward proposition of government bonds. So much so, they challenge conventional assumptions about how bonds should behave and the defensive role they are supposed to play in multi-asset investment portfolios.

Meanwhile, policymakers have the unenviable task of striking a very fine balance. Too little stimulus means a painfully severe recession. Too much risks loss of credibility on inflation control and government debt sustainability.

Faced with all this, it would be imprudent not to at least question whether government bonds are still the ‘safe haven’ they are assumed to be. To question whether interest rate duration is still a reliable hedge for equity risk.

At the risk of stretching metaphors too far, fiscal stimulus is now back in fashion and will remain so until the bond vigilantes (i.e. the fashion police) say, enough!

The term ‘bond vigilante’ was coined by former Yale economist Ed Yardeni in the 1980’s to describe bond investors who push back on excessive government spending by demanding higher risk premia (i.e. higher yields) on government bonds. They may be poised to make a comeback.

The fiscal stimulus unleashed globally over the past few weeks is astounding, both in terms of its speed and its scale. This amount of government spending is rarely seen outside wartime, and it is coming on top of a decade worth of accumulated monetary easing.

While the last decade was dominated by monetary policy, 2020 will be remembered as the year fiscal stimulus became fashionable again.

Right now, investors are entirely focused on the near-term economic damage from virus disruptions, which means markets are applauding every new stimulus program being announced. However, we will eventually reach a tipping point where the consequences of all this policy stimulus will have to be weighed.

What does it mean for government finances, will bond investors start demanding more risk premium, will the bond vigilantes make a comeback?

Can bond markets handle so much new government bond issuance, will longer dated bond yields shoot higher or will central bank buying be enough to maintain the supply vs. demand balance?

At a time when monetary policy is already pushing new extremes, will so much fiscal stimulus cause longer term inflation expectations to shoot higher and what would that mean for the stability of currencies?

No one can answer these questions with certainty, but it is a safe bet that bonds will behave very differently going forward than they have in the past, which in turn has important implications for portfolio construction and the traditional assumption that government bonds are a ‘safe haven’ asset.

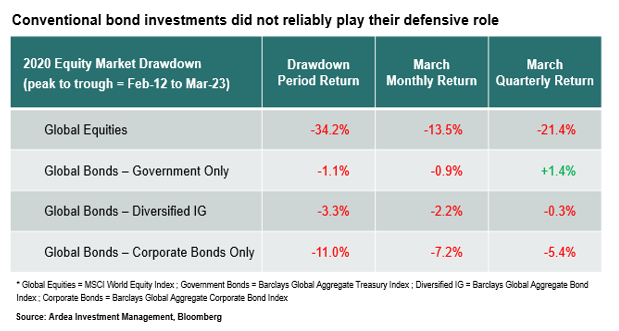

We’re already seeing these dynamics playing out as bonds failed to hedge equity risk reliably during the February / March global equity drawdown – one of the most violent on record.

This changing behaviour of bonds undermines the central assumption underpinning most multi-asset portfolio construction models i.e. that the interest rate duration inherent in government bonds will protect against equity losses.

Given the sheer size of equity market in March, conventional bond investments were supposed to provide decent protection. They did not.

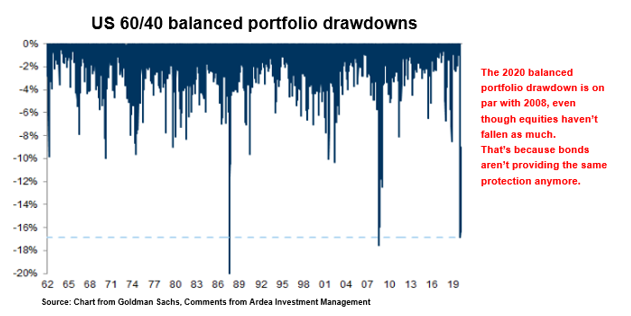

As Goldman Sachs points out, in relation to typical government bond / equity balanced portfolios:

“A 60/40 portfolio had one of the largest drawdowns since the 1960s this month. This was due to the sharp equity drawdown but also as there was less of a buffer and diversification from bonds.

… In addition to the sharper-than-normal equity correction, diversification in 60/40 portfolios has been less good. First, with bond yields at all-time lows now and close to the effective lower bound, there is little space for most DM bnonds to buffer equity drawdowns. In other words, the beta of bonds to equities has declined, especially in Europe and Japan. But also equity-bond correlations turned positive in most markets”

– Goldman Sachs, ‘The 60/40 Drawdown and Multi-Asset Portfolio Risk’, Mar 2020

We have covered these themes before here and here.

Given monetary policy has already gone ‘all in’ and given the avalanche of new government bond supply coming to fund all the promised fiscal stimulus, government bond markets now face the base case scenario of outsized price volatility relative to their meagre returns and the tail risk scenario of future inflation spikes imposing crushing losses on long duration bond exposures.

That is unless central banks everywhere can impose Japan-like control, but with the starting point of government bond yields now at multi-century lows, you’re really not getting paid much to take that bet.

Why has fiscal policy taken over?

While monetary policy is still being deployed aggressively to fight the current crisis, its first order focus is not economic stimulus but rather, restoring liquidity and proper functioning to financial markets. That process began in mid-March, led by the US Federal Reserve (FED), and other central banks have since followed.

The unprecedented scale of central bank liquidity injections and bond buying programs (i.e. quantitative easing – QE) was first aimed at improving liquidity in core interest rate markets (i.e. high-quality government bonds and related interest rate derivatives) and then moved onto addressing more severely dysfunctional credit markets.

They started with core rate markets because, as we saw during the 2008 financial crisis (GFC), interest rate markets need to stabilise and function properly before any other market can. Core rate markets are the plumbing of the financial system, they are the risk-free benchmark from which everything else is priced. They need to function properly before anything else can stabilise.

However, when it comes to the economic stimulus needed to soften the blow from virus disruptions, fiscal policy has taken over because monetary policy had already pretty much reached its limits.

We’ve noted before that ultra-loose monetary policy was like the central bank bar tab that was immediately topped up at the slightest sign of the asset price party waning. (details here)

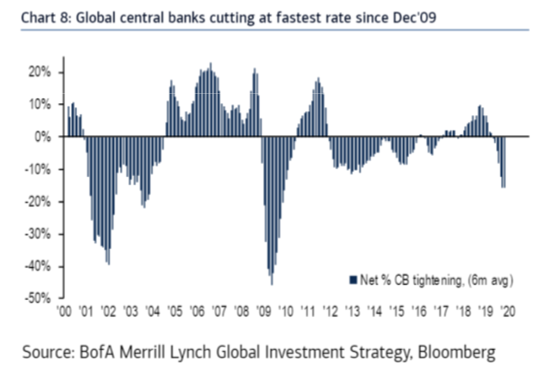

In 2018, central banks led by the FED, tried to reign the party in by starting to normalise interest rates. The partygoers reacted badly, pushing equity markets into, what was at that time, the biggest drawdown since the GFC. Thus 2019 became the year in which financial markets bullied central banks into keeping the bar tab open and letting the party continue. (details here)

In fact, not only did they keep the party going, they ramped it up even more by returning to full scale stimulus mode. Led by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) push deeper into negative interest rates, central banks in 2019 were cutting rates at the fastest rate since the GFC.

The failure to build up an interest rate cushion, by materially raising rates in prior years when economic growth was OK, meant that by the time the virus hit in 2020, the central bank bar tab was already pretty much depleted from an economic stimulus perspective,

Even worse, it became increasingly apparent that the negative side effects of ultra-low rates were starting to outweigh any benefits. Much like the effects of alcohol transitioning from pleasant social lubrication to messy drunkenness, with drunken excess being an appropriate comparison for such incredible developments as ‘junk’ rated bonds trading with negative yields. (details here)

These dynamics were explained in the following article about Sweden’s decision to finally shut the central bank bar tab last year:

“This is also the most explicit signal yet of growing concerns in Europe about the collateral damage and unintended consequences of protracted and excessive reliance on unconventional monetary measures, particularly negative interest rates and large-scale purchases of securities.

The loud Riksbank message to other central banks is that being “the only game in town” for too long can make them not just ineffective but also counterproductive.

If Sweden can hold out as the monetary policy outlier in Europe — and it’s far from easy given the “small country” conditions — this could well be looked back at as the beginning of the end of a historic policy experiment, one that worked initially but was subsequently undermined by the failure of politicians to enable the much-needed pivot to a more comprehensive pro-growth policy response.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Sweden says enough is enough on negative rates’, Dec 2019

And in a similar vein from the Financial Times:

“It is the biggest monetary policy experiment of modern times. One that has divided economists, central bankers and politicians. But now that Sweden has called a halt to its five-year trial with negative interest rates the serious work has begun on looking at whether it worked.

Sweden’s Riksbank, the world’s oldest central bank, was the first to take its main repurchase rate — at which commercial banks can both borrow or deposit money — negative in early 2015, to fend off deflation, only returning to zero in December.

The end of the Swedish experiment is being watched with intense fascination, not just by those central banks that still have negative rates such as the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan, but also by authorities and economists worldwide pondering how to respond to the next downturn with limited ammunition to stimulate the economy.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Why Sweden ditched its negative rate experiment’, Feb 2020

In the post-GFC era, policymakers had become increasingly reliant on monetary stimulus as the policy tool of choice to mitigate economic growth risks, even as there was progressively growing doubt about its continuing efficacy. Making this point, the editorial board of the Financial Times noted the following in January this year:

“For four decades, monetary policy has been the dominant instrument of macroeconomic policy and central banks the queens of macroeconomic policy.

…Today, however, even unconventional monetary policy looks exhausted. Short-term central bank interest rates are close to zero in the eurozone and Japan and a mere 0.75 per cent in the UK. In the US, the Federal Reserve was unable to get rates above 2.5 per cent in the upswing and is now back down to 1.75 per cent.

… Room for action in response to a significant downturn is limited. Historically, the Fed has cut rates by as much as 5 percentage points in response to a recession. That would bring US rates to minus 3.25 per cent. This would only work if depositors could be charged for leaving money in banks.

… Yet there are deeper reasons for rediscovering fiscal policy. The most important is that its side-effects are less bad. Monetary policy works via expansion and contraction of credit, via shifts in asset prices, and via the quantity of a relevant monetary aggregate. The first has generated destabilising credit bubbles. The second can create significant economic distortions. Central banks have lost faith in the last.”

– Financial Times, ‘Active fiscal policy must be part of a new normal’, Jan 2020

So when the virus disruptions hit, there was no choice but for fiscal policy to step up … and it has done so in a huge way.

How much fiscal stimulus is coming?

Governments everywhere have launched a blitz of stimulus measures, the speed and scale of which is astounding.

Based just on what has been announced so far, Morgan Stanley notes the following:

“As a percentage of GDP, the G4+China cyclically-adjusted primary deficit will rise, reaching 8.5% of GDP in 2020, significantly higher than 6.5% in 2009 (immediately post GFC).

In the US alone, we expect the cyclically-adjusted primary fiscal deficit to rise to 13% of GDP in 2020 (assuming a stimulus of US$2 trillion) compared with 7.0% of GDP in 2009.”

The extent of strain on government finances will vary country by country. For example, in the UK Deutsche Bank notes:

“How will governments repay the increase in government borrowing caused by stimulus and deep recession? Our UK economists note the fiscal shock for the UK economy this year will be the third largest in the last one hundred years, behind only increases in borrowing seen in the two World Wars.”

Japan, already having the highest government debt levels among developed economies, has proposed a yet to be approved fiscal package totalling c. 10% of GDP.

In Australia, the fiscal packages announced to date amount to c. 10% of GDP, including $130bn (6.5% of GDP) to directly subsidise wage payments. This exceeds what was spent in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

Other economies have announced more modest packages so far (c. 3-5% of GDP), but these could increase substantially depending on the severity and duration of the economic hit that’s coming.

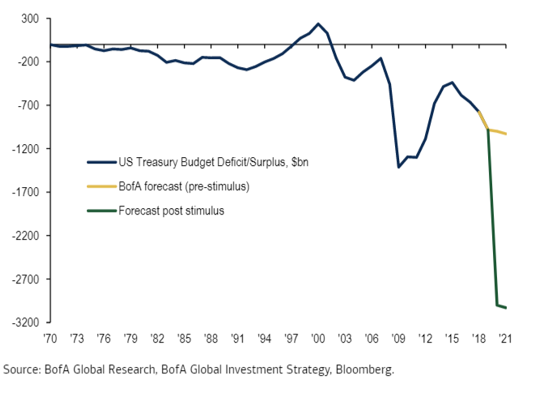

The chart below provides some historical perspective on the sheer scale of government spending announced for the US. While the numbers are given in absolute terms, rather than % of GDP, they still give a sense of how rapidly budget deficits will increase. Similar dynamics are playing out in many countries.

The EU is still finalising its plans but what has already been announced is very large and moving into unprecedented territory such as mutual debt issuance across the Eurozone.

Spain announced fiscal stimulus amounting to 20% of GDP (gigantic!).

Germany has already announced up to EUR550bn of funds for struggling companies, with the finance minister saying, “This is the bazooka … We’re using it to do what is necessary. We’ll check later to see if we need additional smaller weapons.”

In addition, the Financial Times reported – “Germany is set to abandon six years of fiscal restraint with a blowout budget designed to save its economy from the brutal effects of the coronavirus pandemic and protect thousands of businesses from imminent ruin. Angela Merkel’s cabinet is meeting on Monday to approve new borrowing of €356bn — equivalent to nearly 10 per cent of Germany’s gross domestic product — marking a new era in fiscal policy and a radical departure from Berlin’s long-held aversion to debt.”

Angela Merkel said Germany won’t rule out joint European Union debt issuance to help fund EU wide fiscal stimulus. This would be a historic shift that Germany’s fiscal hawks have long opposed and would help integrate the EU more closely. A game changer if it happens.

France announced a guarantee program for EUR300bn of business loans, with Emmanuel Macron saying, “We are at war, and all government and parliamentary forces must be focused on fighting the epidemic”.

Expect much more to come from the EU. In an op-ed article for the Financial Times this week, the still influential former ECB President Mario Draghi wrote:

“The challenge we face is how to act with sufficient strength and speed to prevent the recession from morphing into a prolonged depression, … It is already clear that the answer must involve a significant increase in public debt … Much higher public debt levels will become a permanent feature of our economies and will be accompanied by private debt cancellation”

Private debt cancellation??? Strong (and controversial) stuff!!!

What does this mean for government bonds?

Of course all this fiscal stimulus, which in aggregate is of a magnitude that is unprecedented outside wartime, means governments need to borrow more money by issuing lots and lots of new bonds.

Investors have become used to reflexively reaching for the interest rate duration inherent in government bonds as THE hedge of choice for equity risk, implicitly assuming that highly rated government bonds are by definition a ‘safe haven’.

It’s now prudent to reconsider those assumptions in light of the following factors, which in combination are driving a stark paradigm shift for government bond markets:

- Demand / supply imbalance

Even prior to the virus, bond markets had already experienced a huge rally through 2019, while equities also reached new record highs (i.e. a positive correlation), both being heavily supported by the ‘low rates forever’ narrative.

This strong consensus narrative catalysed record inflows to bonds despite a large proportion of the bond market offering negative yields, raising questions about already crowded consensus positioning in bond markets. (details here)

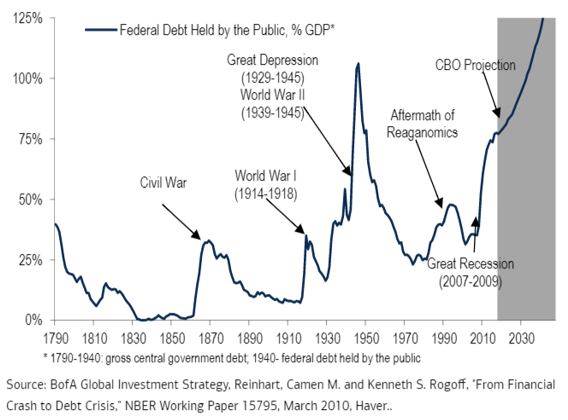

This naturally leads to the question of how well bond markets can absorb the vast amounts of new government bond supply that is coming. Recall that when Japan was ramping up its government spending, on its way to becoming the most indebted developed economy in the world, it had a giant domestic pension savings pool to absorb it.

We are now about to see rapidly rising government debt levels at a time when ageing populations in the western world are transitioning into retirement and drawing down their retirement savings. This may mean less demand from pension savings pools to absorb all those new bonds.

Lots of new government bond supply, at record high prices, isn’t an ideal combination when demand may be waning.

- Government debt concerns

Rapidly rising government debt levels will eventually focus attention on the state of government balance sheets and sovereign credit risk. As Deutsche Bank notes:

“If the shutdowns of major economies go on for as long as is starting to be feared then it’s likely that governments are going to see deficits of this magnitude through fiscal injections, automatic stabilisers and loss of revenues. We would expect that the only way of calming people and markets around this is for pure helicopter money where central bank’s balance sheets balloon to absorb the increased debt. This will lead to a permanent scar on government balance sheets that were already stretched.”

This will be more of an issue in some countries than others and is highly contingent on the severity/duration of the economic disruptions to come.

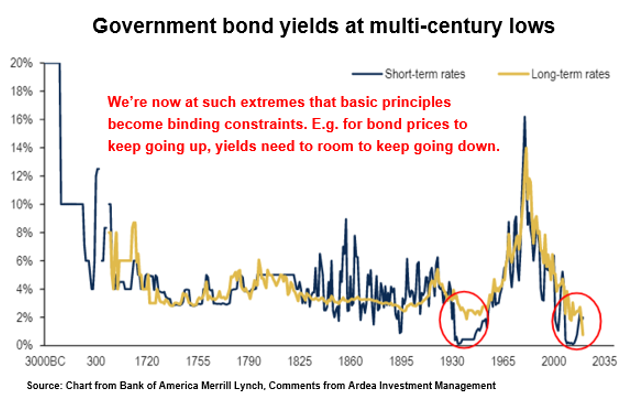

- Lower bound for rates

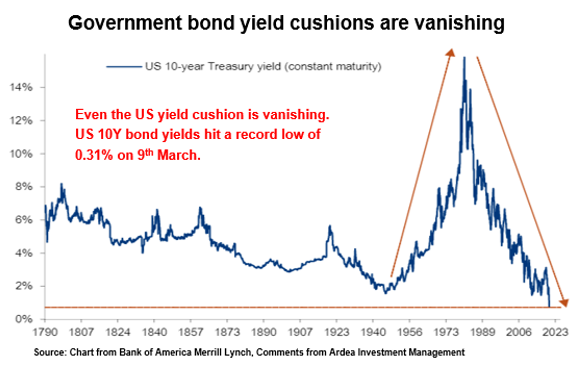

With cash rates in most developed economies now effectively at the lower bound (i.e. near or even below zero) and a growing acceptance of the unsavoury side effects of negative rates, the single biggest tail wind for government bond markets – central bank rate cuts – is now pretty much done.

Therefore any further upside in bond prices (i.e. falling yields) is now highly conditional on yield curves being able to flatten further from already historically flat levels (i.e. longer dated bond yields falling relative to short term rates).

Of course they could keep flattening, but that is far from certain because it would require bond investors being willing to accept even lower risk premia for duration risk, despite being faced with large new bond issuance, stretched government finances, inflation uncertainty etc.

We’re at such extremes now that basic principles become binding constraints … for bond prices to keep going up, yields need room to keep going down.

- Inflation tail risk

The current consensus view is that inflation is dead forever. This view may be tested by the unprecedented combination of massive fiscal stimulus + ultra-loose monetary policy + risk of supply side production disruptions, that we now have.

Given the ultra-low starting point of bond yields, an unexpectedly rapid rise in future inflation would be very damaging for bond markets. This is explored in more detail below.

To put things in perspective, the chart below shows how large the government debt burden will become for the US alone. The same dynamics are set to play out in globally, to varying degrees.

And this all happening at a time when the yield cushion that protects against the duration risk inherent in government bonds is extraordinarily low. Even in the US, where the FED managed to rebuild a modest yield cushion by raising rates in 2018, yields have dropped all the way back toward zero. (refer here for an explanation of yield cushions).

Bond yields could go negative everywhere, as they already are in Germany and Japan, but as explained earlier, negative rates seem to be falling out of favour now.

Combining all these factors, price sensitive bond investors will eventually demand more of a risk premium (i.e. higher bond yields) in return for taking the duration risk inherent in government bonds. Remember, even with central bank cash rates anchored at zero, longer dated bond yields can still rise.

We already saw early signs of this in March:

“Global bonds plunge on fear of debt deluge from pandemic defence. European sovereign bonds led a global rout as markets braced for the kind of supply surge not seen for years, after nations from the U.K. to France and Italy unveiled plans to spend their way out of the coronavirus crisis.

Investors are pricing in the risk of a surge in government borrowing to fund stimulus aimed at offsetting the economic shock from the pandemic.”

-Bloomberg News, 18th March 2020 “The Treasury market buckled Tuesday at the prospect of a flood of U.S. spending to fend off an economic nightmare… Rates on 10- and 30-year bonds shot up more than 36 basis points, their biggest one-day increases since 1982… The surge in yields is in response to the massive supply pressure on the way, rather than any expectations for a recovery in growth or inflation”

-Bloomberg News, 17th March 2020

And ‘safe haven’ government bond prices are exhibiting equity like volatility. For example, US 30-year government bonds have been experiencing 9% intra-day price swings and dropped 17% over 7 days in March, before partially rebounding.

Fighting against all this is and the potential saviour of government bonds is one group of enormous price insensitive buyers … central banks.

Thus, we’re set up for a 3-way showdown between the governments, who will be dumping more and more debt onto government bond markets, the private investors, who will demand higher risk premia to keep buying all those bonds and the central banks, who will need to be the buyer of last resort to prevent a violent re-pricing of bond markets (i.e. higher yields / lower prices).

The government bond markets that benefit from a high representation in reserve currency holdings have the best prospects for navigating these conflicting forces (USD, EUR, JPY), while the others could get messy.

What’s the end game?

Japan provides a blue-print for the benign (at least so far) end game scenario.

Despite enormous government debt, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has successfully kept bond yields under control via aggressive market intervention. While there is much criticism about the longer-term merits of their approach, the fact remains the BOJ has been able to keep bond yields pinned at extraordinarily low levels, while facilitating very large amounts of government bond issuance.

The question then becomes, can the Japan experience be repeated everywhere else, all at once?

Whether it’s the right approach or not in the long term, central banks will certainly try very hard to keep government bond yields pinned down. Otherwise, if bond yields were to rise a lot, at a time when inflation expectations remain subdued, the resulting increase in real yields would effectively represent a monetary policy tightening. That’s the last thing they want when governments are frantically deploying fiscal stimulus to prevent a prolonged recession.

We’re already seeing some central banks move along the path toward BOJ style market intervention. For example, the FED has now made its QE program open ended (i.e. unlimited bond buying) and Australia’s central bank has announced an explicit target for 3-year bond yields.

How well this works as the new bond supply deluge hits remains to be seen.

A longer-term consideration is that when central banks aggressively intervene in bond markets, bond prices lose their information value, as we have already seen in Japan.

Bond market pricing normally acts as a disciplinary check on the actions of central banks and governments. For example, if monetary policy is too loose and inflation risk is rising, or if government borrowing is becoming unsustainably high, bond markets will reflect this via the risk premia incorporated in pricing.

Aggressive central bank intervention dampens these pricing signals, which means inflationary pressures, unsustainable debt levels etc. can continue building up without any market based disciplinary check. It’s therefore then left entirely up to central bankers and governments to control themselves.

How confident can we be that a small group of powerful policymakers with little real-world accountability, can walk the delicate balance between too much or too little policy stimulus?

Of course the policymakers would like us to believe very confidently in their abilities.

Back in 2015, BOJ governor Kuroda began a policy speech explaining the BOJ’s extreme monetary policy stance by invoking Peter Pan:

“I trust that many of you are familiar with the story of Peter Pan, in which it says, ‘the moment you doubt whether you can fly, you cease forever to be able to do it,’”

As monetary policy increasingly reaches its limits and, as some argue, with little results to show other than rampant asset price inflation, the power of central banks becomes increasingly reliant on markets continuing to believe in their words, in their narratives, rather than concrete positive impacts of their actions.

‘I believe I can fly’ might be confidence inspiring to some but sounds delusional to others. In that same vein, many of the consensus narratives around central bank omniscience and omnipotence will now be severely tested.

The catchphrases that have dominated the past decade (‘don’t fight the FED’, ‘central banks to the rescue’, ‘the FED put’, Draghi’s famous ‘whatever it takes’) may be much less potent going forward than they have been in the past.

The ultimate test of belief in central bank credibility may well be the end game we are heading for – debt monetisation.

This seemingly innocuous technical term is in fact loaded with all kinds of scary connotations as it refers to the controversial idea of central banks explicitly financing government spending by printing money to absorb extreme levels of government bond issuance that markets wouldn’t be able to digest (at least not without yields rocketing higher).

This is controversial because of the fear that it could eventually lead to economic carnage via hyperinflation, sky high interest rates and loss of confidence in currencies a la Venezuela, Zimbabwe etc.

Again, it is those countries whose government bond markets have a high representation in reserve currency holdings that can navigate this best.

Debt Monetisation: Will one lead to the other?

A recent paper co-authored by former FED vice chair Stanley Fischer argues that ‘unprecedented policy co-ordination’ will be needed to fight the next economic downturn. Recognising the risks of outright debt monetisation, the authors advocate a middle path of fiscal and monetary policy co-ordination that mitigates these risks. While that sounds fine in theory, in practice it requires policymakers to manage an extremely delicate balance in engaging extraordinary stimulus measures, while still maintaining a credible narrative around inflation and budget deficit control.

Such narratives only hold as long as the majority thinks that the majority still believes in them. Once that belief is questioned a dramatic paradigm shift can occur. The early warning signal will be a modest but sustained increase in longer dated bond yields. Initially it will be subtle enough that most won’t notice (aside from the bond vigilantes), but then it quickly gains momentum as confidence in the prevailing narratives crumbles.

What does this mean for inflation?

Back in 2008, when the US Federal Reserve cut interest rates aggressively and began its first QE program, some feared this would lead to rampant inflation and the ultimate debasement of fiat currencies.

Yet, despite many more rounds of rate cuts and QE since then, traditional measures of consumer price inflation in most developed economies have only fallen, and deflation rather than inflation became the main concern. Japan is the most extreme example of ultra-loose monetary policy failing to produce inflation.

So, could this time be different?

It is impossible for anyone to reliably predict whether inflation will increase from here or not, given the complex web of variables and feedback loops involved.

A more useful approach is to understand what the current consensus views are and the extent to which they are already being reflected in current market prices. We can then think about how those consensus views might be challenged and what the resulting impact on future market prices might be.

For inflation across developed economies, the consensus view is clear – inflation is dead and won’t be resurrected any time soon. We covered this in detail here.

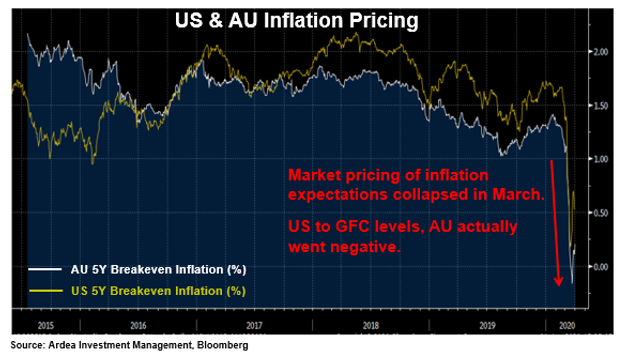

In terms of market pricing, even prior to March this consensus view was already being heavily reflected in the pricing of inflation linked government bonds. The March turmoil took things to a whole another level.

For example, the chart below shows a rough proxy for the market pricing of inflation expectations based on 5 year Australian and US government inflation linked bonds (known as the ‘breakeven inflation’ rate).

The US collapsed close to zero in March, before rebounding to a still very low 0.5%, while Australia actually went negative and is still stuck close to zero. Australian breakeven inflation rates effectively imply a prolonged disinflationary scenario that lasts for the next 5 years.

While it’s easy to understand that recession fears are dampening near term inflation expectations, even very long dated inflation linked bonds are implying ultra-low inflation for a very long time. E.g. Australian 10 year breakeven inflation rates are c. 0.5% and 20 year c. 0.9%. (For context, actual CPI inflation in Australia has ranged between 1% and 3.5% over the decade)

So, our starting point today is a very strong consensus view of ultra-low inflation for a very long time, and this is already heavily reflected in current market pricing. In betting terms, markets are pricing the ultra-low inflation scenario as the extreme odds on favorite, while even modest inflation increases are priced as a very remote possibility.

Any ‘relative value’ focused investor looking at this would immediately see the makings of a favorably asymmetric investment opportunity (i.e. limited downside risk vs. large profit potential). The only missing ingredient is a catalyst.

Which takes us back to the original question – could this time be different to the past decade? These points are worth considering in answering this question.

- Monetary policy is ‘all in’

The sheer scale of monetary policy easing we’re now seeing has gone far beyond what we saw in response to the GFC. Central banks globally are now ‘all in’ on monetary stimulus, with the largest among them explicitly stating they will do ‘whatever it takes’ to mitigate near-term downside risks to economies and financial market stability. (note the emphasis on near-term vs. long-term)

Per Bank of America estimates, the big 5 central banks (ex-China) have bought c. $13 trillion of financial assets in total since the Lehman default in 2008. They are set to buy another $7 trillion just this year alone and have left open ended commitments to buy unlimited amounts more.

In the entire 11 years since Lehman defaulted, central banks have cut rates 853 times. 65 of those cuts happened in just the last 3 months.

The scale aside, they are pushing further into uncharted territory by scrapping existing self-imposed limits on the scope of their asset purchases. For example, the FED has committed to unlimited buying of corporate debt and the ECB has scrapped limits on the breadth of EU assets it can buy. It’s unclear where are all this ends.

- Fiscal policy is ‘all in’

As explained earlier in this article, we now have global fiscal stimulus of an unprecedented magnitude outside of wartime. We did not see this in response to the GFC, and in fact from 2010 onward the focus was more on fiscal austerity in most countries.

The transmission mechanism from fiscal stimulus to inflation is complex and unclear.

Conventional economic theory suggests inflation is largely a monetary phenomenon and has less to do with fiscal policy. But that same conventional thinking has failed to explain why inflation has remained so stubbornly low for the past decade. Newer schools of thought suggest the relationships between monetary policy, fiscal policy and inflation are more complex and less predictable than previously believed. (for example, How fiscal policy drives inflation.)

- Policy co-ordination is ‘all in’

Compared to the GFC response, we’re now seeing much more co-ordination between fiscal and monetary policies in most countries. Some argue the reason policymakers failed to raise inflation to their targets post-GFC was precisely due to a lack of policy co-ordination. In fact, in some ways fiscal policy, with a focus on balanced budgets, was working in the opposite direction to monetary policy.

Now we have policy co-ordination going to other extreme with talk of debt monetisation, as described earlier, and even ‘helicopter money’, which many fear could be highly inflationary.

“Hong Kong permanent residents aged 18 and above will each receive a cash handout of HK$10,000 (US$1,200) in a HK$120 billion (US$15 billion) relief deal rolled out by the government to ease the burden on individuals and companies, while saving jobs.

… Much touted but seldom tried, economists have long seen helicopter money as the most radical tool that central bankers could deploy to fight a weak economy…

However, in these latest instances it’s the politicians leading the charge. We are not sure whether that would happen in somewhere more fiscally conservative, such as Northern Europe, or whether it would fall on the shoulders of the European Central Bank. Hopefully, we will not need to find out.”

– Financial Times, “Helicopter money is here”, Feb-2020

- Nothing is off the table

We are now seeing previously fringe policy ideas getting serious mainstream attention, most notable of which is Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Without delving into all the complexities, the basic idea of MMT is that a government can raise unlimited amounts of debt in its own currency and then simply print more money (via the central bank) to pay off those debts.

It’s an idea from the 1940’s that now has high profile advocates in places like the US Democratic Party, even though prominent mainstream economists and policymakers dismiss it as dangerously experimental.

The binding constraint on MMT, as its own proponents explicitly acknowledge, is inflation. Central banks printing money to fund government expenditure can quickly become dangerously inflationary if central banks lose credibility on their inflation control narrative. MMT proponents offer various ideas to manage the inflation risk (e.g. tax increases, enforced savings policies) but none have been tested.

The big risk is that recency bias (i.e. the recent experience of low inflation) emboldens politicians to aggressively push for policy approaches like MMT in the (mistaken) belief that inflation risk is too remote to worry about.

- Supply side disruptions

This is the wildcard. Right now all the attention is on demand destruction from virus related unemployment, loss of consumer confidence etc., which together with the collapse in oil prices are all deflationary forces.

However, what’s not getting much attention yet is the disruption to global supply chains from border restrictions, worker mobility constraints, rising aversion to global trade etc. As Ken Rogoff points out, this is what the upcoming recession different:

“But policymakers and altogether too many economic commentators fail to grasp how the supply component may make the next global recession unlike the last two. In contrast to recessions driven mainly by a demand shortfall, the challenge posed by a supply-side driven downturn is that it can result in sharp declines in production and widespread bottlenecks. In that case, generalised shortages – something that some countries have not seen since the gas queues of 1970s – could ultimately push inflation up, not down.

Admittedly, the initial conditions for containing generalised inflation today are extraordinarily favourable. But, given that four decades of globalisation has almost certainly been the main factor underlying low inflation, a sustained retreat behind national borders, owing to a Covid-19 pandemic (or even lasting fear of pandemic), on top of rising trade frictions, is a recipe for the return of upward price pressures. In this scenario, rising inflation could prop up interest rates and challenge both monetary and fiscal policymakers.”

– Guardian, “A coronavirus recession could be supply-side with a 1970s flavour”, Mar-2020

One historical analogue is post-war recovery periods, which show that the natural demand recovery after a period of extreme restrictions, combined with massive fiscal and monetary stimulus, created inflation in the range of 5-10% or even higher.

Considering all these factors, we now see everything being thrown at averting near term economic growth risk, with little consideration of the longer-term consequences. Applying this to inflation risk, the tomato sauce bottle analogue comes to mind.

History shows that when inflation expectations change, they can change very quickly. Right now, all the policy measures being implemented are anti-cyclical (i.e. they are dampening downside growth risks) but they risk turning highly pro-cyclical because of the ‘sudden stop’ nature of this economic shock.

Unlike the gradual process of decline we see for most recessions, this one is happening very suddenly. For example, the US has swung from record low unemployment to off-the-charts record high jobless claims in just a few weeks. Therefore, it is possible that the recovery on the other side is also very fast, particularly if all these policy measures are effective in preventing temporary corporate liquidity problems from turning into permanent solvency ones.

Given the time lags between policies being implemented and their full effects being felt, in a quick recovery scenario this avalanche of policy stimulus will become highly pro-cyclical. By that time, policymakers will be stuck in an unprecedented stimulus cycle that they can’t easily reverse, without causing huge disruptions. For example, recognising that overleveraged economies will be too fragile to stomach quick interest rate hikes and perhaps also hindered by recency bias – when you’ve spent a decade trying and failing stimulate inflation, it’s hard to quickly shift your mindset back to curbing it – central banks will necessarily be slow to raise rates even as they see inflationary pressures building.

Combine this pro-cyclicality with populism, which is giving workers more bargaining power and possible lasting constraints on the free flow of cheaper migrant labour, you can see how rapidly the prevailing low inflation narrative can change.

At that point, long duration government bonds yielding less than 1% will look as absurd as junk bonds trading with negative yields did last year.

Of course, none of this is certain and no one can reliably forecast future inflation. So the way to think about this is in probabilistic terms and expected payoffs in different scenarios.

Going back to our starting point today – i.e. a strong consensus view of ultra-low inflation forever, that is already heavily reflected in current market pricing – inflation securities are already pricing the low inflation scenarios with a high probability and therefore the payoff is low if that scenario occurs, but they are pricing the higher inflation scenarios with very low probability, giving a high potential payoff if they occur.

Therefore, we can conclude that pure inflation exposure (i.e. without the interest rate duration risk of conventional inflation linked bond holdings) currently offers favorably asymmetric profit potential.

And remember, to profit from this opportunity we don’t need actual inflation to rise in the near term, we only need the prevailing narrative of ‘ultra-low inflation forever’ to shift modestly toward recognising even some risk of higher future inflation.

Given all the potential catalysts outlined earlier, it doesn’t take much imagination to see how this narrative shift could take place and we’re already seeing signs of it starting:

“In a matter of weeks, bond investors have seen some of their firmest market convictions swept away in a massive confluence of government stimulus and central bank intervention. Now, they’re being forced to rework their strategies for a new era.

Core tenets such as what constitutes a safe asset, the value of bonds as a portfolio hedge, and expectations for returns over the next decade are all being reconsidered as governments and central banks strive to avert a global depression.

Underlying much of the uncertainty is the risk that trillions of dollars in monetary and fiscal stimulus could create an eventual inflation shock that will trigger losses for bondholders.”

– Bloomberg News, ‘Infinite QE Is Destroying Traditional Bond-Fund Strategies’, Mar 2020

Implications for portfolio construction

Policymakers now face the unenviable task of striking a very fine balance. Too little stimulus risks a painfully severe recession. Too much risks loss of credibility on inflation control and government debt sustainability.

Economists and market watchers have long speculated about what the end game would look like if governments piled fiscal stimulus on top the past decade’s worth of accumulated momentary stimulus. Now we’re about to find out.

The takeaways here are not binary. It’s not about which way bond yields will move from here or whether future inflation will be higher or lower. Nobody can reliably predict these things.

For multi-asset portfolios, it’s about a nuanced re-assessment of how government bonds are expected to behave, an objective scrutiny of how reliably they can continue to play their defensive role and balanced consideration of the tail-risk scenarios that might play out from the unprecedented policy actions being implemented.

The fact the government bonds have failed to provide decent protection during one of the largest equity drawdowns since the GFC should be a big warning sign.

Adding this to the current set up of unprecedented global fiscal stimulus, extreme monetary policy experiments, yields at multi-century lows and inflation tail risks, it would be imprudent not to at least question whether government bonds are still the ‘safe haven’ they are assumed to be. To question whether interest rate duration is still a reliable hedge for equity risk.

The inflation tail risk scenario is particularly relevant for multi-asset portfolio construction.

For a decade now we’ve mostly had a ‘good inflation’ narrative, in which inflation is seen a positive side effect of stronger economic growth. But the experience of 2018 shows how quickly ‘good inflation’ turns into ‘bad inflation’, causing turmoil for bond markets and flipping bond/equity correlations from negative to positive.

As Morgan Stanley pointed out just before the virus hit:

“At present, we think investors are either sceptical of a sustained rise of G3 inflation, or would welcome it, a sign of better growth and returning normality. Our economic forecasts also have inflation rising in 2020, but central banks effectively embracing that rise with no change in policy.

But it is not that long ago, in 2018, when markets viewed a rise in inflation as more problematic. In 2019, every asset has rallied. But in 2018, almost every asset declined, and markets began to worry that excess capacity in the global economy was being used up. Inflation is a risk to our narrative that we need to watch.”

– Morgan Stanley, ‘Cross Asset Dispatches’, Dec 2019

Inflation increases the tail risk volatility of government bonds, which therefore increases the volatility of multi-asset portfolios that combine bonds and equities. As Goldman Sachs explains:

“S&P 500 returns historically have not been normally distributed – the distribution of daily returns reveals that equities have ‘fat’ tails, or high excess kurtosis since 1990. In recent years, that has resulted in material tail risk for 60/40 portfolios. In the late 1960s and the 1970s, US 10-year bonds actually had higher excess kurtosis due to inflation shocks, which drove tail risk in multi-asset portfolios.

… due to the decline in inflation volatility (and central bank inflation targeting), global real yields have declined significantly since the mid-1980s, which in turn has boosted valuations across assets due to an intense search for yield.

And falling real yields helped balance bear markets, resulting in a persistent negative equity/bond correlation, and reduced deleveraging pressure.

On the flipside, rising real yields — either due to a major deflationary shock such as during the Great Depression or due to market repricing inflation risk like in the 1970s — would likely weigh on most assets and could drive a material drawdown in balanced multi-asset portfolios.”

– Goldman Sachs, ‘The 60/40 Drawdown and Multi-Asset Portfolio Risk’, Mar 2020

This material has been prepared by Ardea Investment Management Pty Limited (Ardea IM) (ABN 50 132 902 722, AFSL 329 828). It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Any projections are based on assumptions which we believe are reasonable, but are subject to change and should not be relied upon. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Neither any particular rate of return nor capital invested are guaranteed.