Compensation for credit risk is poor

Key points

- Credit investments are neither inherently good or bad; rather it’s the balance between risk and return that matters

- While credit investments such as corporate bonds offer the potential for higher yields than government bonds, they also come with greater downside risks in adverse environments

- The prevailing low interest rate environment has forced enormous yield chasing capital flows into credit markets that have pushed compensation for credit risk to very low levels

- At the same time, credit spread volatility is increasing and average credit quality is decreasing, particularly in the purportedly ‘safe’ investment grade segment

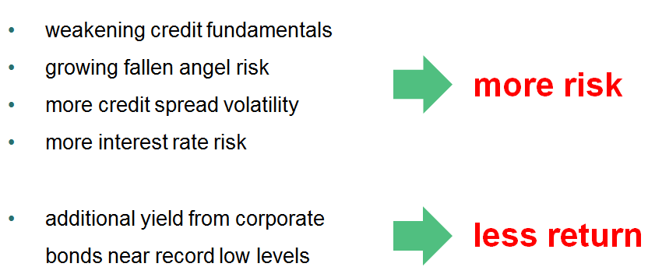

- This has left corporate bond investors poorly compensated for the growing credit risks that they are exposed to and facing the prospect of more risk for less return

- The underappreciated risk is the structural deterioration in corporate bond market liquidity, which has so far been masked by large inflows, but risks triggering a disorderly sell-off if flows turn

- In the context of a broader investment portfolio, credit investments carry ‘latent equity beta’, which can cause them to incur losses in downside scenarios, just as equities are also falling

- From a portfolio diversification perspective, corporate bonds are widely perceived as being defensive investments, but the reality can be very different, as we got a small taste of in Q4 2018

Introduction

Following the sharp sell-off in Q4 2018, credit markets globally have performed strongly in 2019. Having seen a big dip, followed by a quick rebound, how are we now left?

Since the 2008 financial crisis (GFC), credit markets have been in a real sweet spot. On one side they’ve had huge capital inflows from yield chasing investors and on the other side, companies were happy to take full advantage of this demand by issuing lots and lots of debt.

In fact, over the past 10 years companies have raised more debt at cheaper levels in bond markets than at any other time in modern history.

It was a perfect match. Yield chasing investors met debt hungry companies and both sides were happy.

But that was then. The current situation is very different.

Credit markets are now at the point where late cycle risks are becoming more apparent, credit quality is deteriorating and compensation for credit risk has declined as yields have collapsed.

In short, credit investors now face a lot more risk, for a lot less return.

Heading into the GFC, a lot of the debt build-up was in the household sector (think US subprime mortgages) and it was banks who took the hit on their balance sheets when it fell apart. This time around the debt build-up is in the corporate sector. Company debt levels have never been higher and most of this growth has been in corporate bonds, many of which sit in funds sold to retail investors.

Corporate bonds, or any investment for that matter, are not inherently good or bad. Rather, it’s the balance between risk and return that matters.

We’re now at a point in the cycle where the risk vs. return trade-off in corporate bonds is asymmetrically poor. This is the cyclical perspective.

There is also a secular theme that has been playing out behind the scenes since 2008 – liquidity deterioration.

Liquidity in corporate bond markets has been structurally compromised and this is the black swan risk that could trigger a disorderly sell-off in corporate bond markets, which would then spill over into other markets and potentially tip economies into recession.

To be clear, this is a general discussion about blunt credit beta exposure of the type that dominates in a conventional bond portfolio. No doubt there are skilled active managers out there adopting unconventional approaches to ferret out some pockets of value, but even that’s becoming harder as yields head relentlessly lower.

This comment from strategists at BofA Merrill Lynch (somewhat depressingly) sums up the current situation for conventional yield focused bond portfolios;

“Following plunging global yields 10-year government bonds are now yielding -50bps in Switzerland, -25bps in the Eurozone, -12bps in Japan and +207bps in the US.

How are you going to earn at least something in fixed income? Buy corporate bonds.”

– BofA Merrill Lynch Credit Market Strategist, 10th June 2019

If your approach to fixed income investing is to simply accumulate bonds for yield, then sadly they’re probably right … buying corporate bonds is the least bad option currently available.

However, as we tell our investors, there’s more to fixed income than just buying bonds. Even when yields are very low, there are other ways generate attractive risk-adjusted returns from a defensive fixed income portfolio, without resorting to adding more credit risk.

Corporate bond markets matter to all investors

Global credit markets are diverse, ranging from plain corporate bonds, to loans and more esoteric structured credit investments. This article focuses specifically on corporate bonds (i.e. bonds issued by companies) because they are most prevalent in conventional credit and diversified fixed income portfolios.

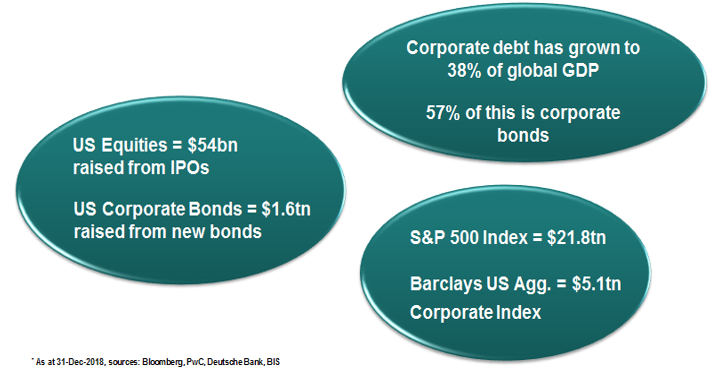

Corporate bond markets are very large and have been growing quickly. Corporate debt globally has never been higher and most of this now sits in corporate bonds.

While equity markets get most of the attention, corporate bond markets are essential for the health of the corporate sector and broader economies. This is because companies right across the economy rely on bond markets to fund their day to day operations.

The amount of capital raised in corporate bond markets each year dwarves what’s raised via equities, despite the market capitalization of equities being larger.

This is because a constant refinancing need exists in bond markets. Unlike equities, which have an infinite lifespan, bonds have a fixed maturity date. So, when a bond matures, the issuer needs cash to repay bondholders and this cash is often raised by issuing another bond.

This is why reliably functioning corporate bond markets matter a lot, even if you’re not a fixed income investor. If these markets break down, economies can’t function properly.

The benefits of investing in corporate bonds

Before discussing the current risk vs. return dynamics in corporate bonds, it’s important to acknowledge the general benefits they can offer as part of a broader investment portfolio.

The primary benefits are the potential for higher returns and some diversification value, outside of very adverse market environments.

The investment consulting firm Mercer, explains it this way;

“While government bonds provide a means for individual investors to lend to governments, corporate bonds provide a means of lending to large corporations. A corporate bond is issued by a corporation to raise money to fund or expand its business. Individuals can loan money to the corporation by purchasing their bonds. In return, the corporation pays the individual interest on the bond, and returns the full value of the bond at a fixed redemption date.

Corporate bonds tend to provide higher interest payments than government bonds due to their higher level of risk. Lending to companies is usually riskier than lending to most developed world governments, as companies are generally believed to be more likely to default. Corporate bonds are thus likely to perform worse than government bonds in bad economic times.”

The underlying principle is that the additional yield offered by corporate bonds – known as a ‘credit spread’ and measured as the yield differential between corporate and government bonds – represents compensation for the higher credit risk investors are exposed to.

Both ‘credit risk’ and ‘credit spreads’ are explained in the appendix at the end of this article.

Compensation for credit risk is currently poor

Compensation for credit risk is central to the value proposition of corporate bonds as investors need to balance the trade-off between higher yields and taking more credit risk.

The attractiveness of that trade-off varies as the additional return offered by corporate bonds fluctuates and credit risk also changes with economic cycles.

Unfortunately, we’re now at a point where compensation for credit risk has collapsed to very low levels, while at the same time, the credit risk side of the equation has also deteriorated, leaving corporate bond investors facing more risk for less return.

How did we get here? The story begins ten years ago.

Following the GFC, years of ultra-low interest rates created an immense yield chasing party across global credit markets.

As the returns offered by lower risk assets followed interest rates toward zero, a great rotation of capital began. A wall of money progressively moved up the risk spectrum, into riskier and riskier assets, in search of higher returns … the so called ‘reach for yield’.

In fixed income markets, yield hungry investors were forced to rotate out of cash deposits and government bonds into progressively riskier credit securities across global corporate bond and loan markets.

In the early stages of this process the stars were aligned, as credit spreads were wide enough to compensate not just for default risk but also offer generous risk premia on top of that. At the same time, companies were eager to issue more debt at low interest rates, providing an ample supply of credit assets to satisfy investor demand.

During this period credit risk was actually very well compensated and allocating to corporate bonds was a great trade for investors … but things have now changed

As the era of ultra-low rates rolled on, turbo charged by quantitative easing, investors became increasingly desperate for anything that offered more yield and therefore equally willing to de-prioritise the risk side of the equation.

As more and more yield hungry investors flooded into credit markets, the demand for corporate bonds forced prices higher and therefor yields / credit spreads lower.

This was a great environment for debt seeking companies because they were able to borrow lots of money very cheaply by issuing bonds to yield chasing investors.

A similar dynamic played out back in 2006 when European auto companies like BMW and Daimler took advantage of yield chasing demand to borrow in bond markets at rates not much higher than where the German government was issuing bonds, despite the auto companies carrying much more credit risk.

Back then, those were warning signs that credit markets were severely under-pricing risk … and just a couple of years later those same credit markets were panicking about large auto companies collapsing in the economic downturn.

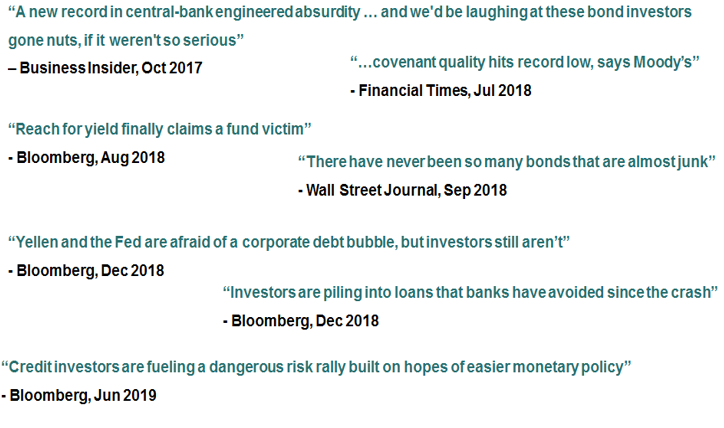

Today we’re seeing similar signs of credit risk being under-priced, with these headlines giving a taste of what’s going on.

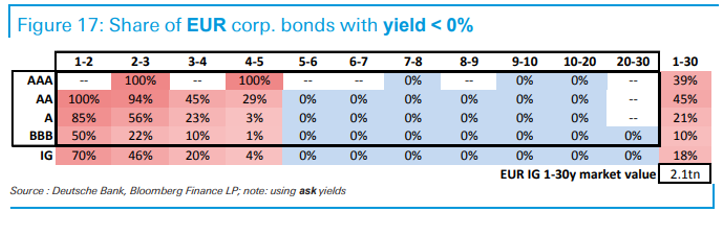

More egregious examples can be found in European credit markets, where negative interest rates have forced yield hungry investors into alarming behaviour.

Examples include corporates, such as ‘BBB’ rated Veolia Environment, being able to issue bonds at negative yields;

“Veolia has issued a 500 million 3-year EUR bond (maturity November 2020) with a negative yield of -0.026 %, which is a first for a BBB issuer.”

– Veolia press release, Nov 2017

And even high risk junk rated bonds (i.e. those with a credit rating below investment grade), are now starting to trade with negative yields;

“The number of euro-denominated junk bonds trading with a negative yield — a status until recently associated with ultra-safe sovereign borrowers — now stands at 14, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. At the start of the year there were none.”

– Bloomberg News, Jul 2019

The table below from Deutsche Bank shows that 18% of the entire EUR investment grade bond market now has NEGATIVE yields and even in the lowest quality ‘BBB’ rated segment of the market, 50% of short dated bonds have negative yields.

It’s hard enough to understand government bonds with negative yields. Corporate bonds doing the same is incomprehensible and suggests any remnant of sensible risk pricing is now gone.

With the ‘reach for yield’ party in full swing across global credit markets, this seems like the kind of behaviour you might see towards the end of a big night out. Seems like a good idea at the time but the next morning … not so much.

We covered the topic of negative yielding bonds here and the effect of ultra-low rates on investor behaviour here.

The examples from Europe cited above are some of the more extreme examples, but even other credit markets have headed the same way.

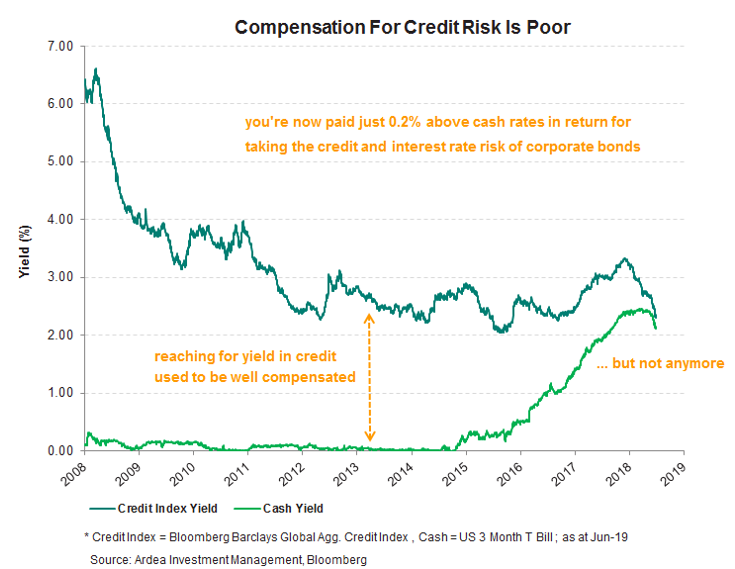

The chart below compares the yield on a widely referenced global corporate bond index to risk-free cash rates. It shows that the extra yield available from corporate bonds has declined to just 0.2% above cash rates … that’s all you get in return for taking materially more credit risk, in addition to significant interest rate risk (remember, corporate bonds carry both risk).

It’s striking just how little compensation for credit risk is now left across global corporate bond markets.

It’s hard to see how an extra yield of just 0.2% is adequate compensation for the extra credit and interest rate risks investors are exposed to in corporate bond markets.

Of course, the chart only shows a broad based index and therefore hides the small pockets of idiosyncratic value that might still be left, but the point still remains that corporate bond market beta exposure currently offers a poor risk vs. return trade-off.

Reaching for yield in credit used to be well compensated but now the easy money is gone. There is little risk premia left across global corporate bond markets, and in many cases not even sufficient base line compensation for default risk. (refer to the appendix at the end of this article for further details)

What this brings to mind is a well-known Warren Buffett quote;

“What the wise do in the beginning, fools do in the end.”

Given the pressure on investment managers to increase returns in a low rate world, the word ‘fool’ is too harsh. Perhaps ‘desperate’ is more appropriate.

Credit risks are rising

Against the backdrop of declining compensation for credit risk, the risk side of the equation is increasing as the average credit quality of corporate bond issuers is getting worse, particularly in the ‘safe’ investment grade (IG) bond space.

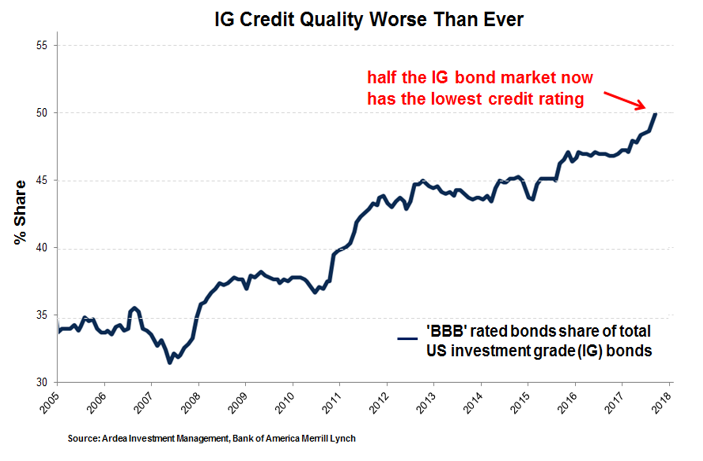

Charts like the one below are getting more attention for good reason. Half the IG bond market is now sitting at the very low end of the IG credit rating spectrum. In fact, average IG credit quality has never been worse.

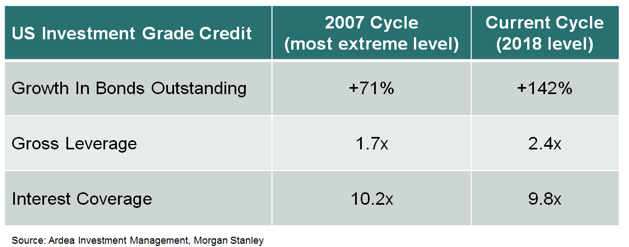

The table below shows worsening credit quality metrics, when comparing the current cycle to the worst levels seen prior to the 2008 financial crisis.

J.P. Morgan’s research team noted the following in a report covering rising ‘net debt to EBITDA’ ratios (a measure of corporate leverage);

“This leverage metric has been rising steeply over the past decade to levels that are much higher than those seen at the peaks of the previous two cycles in 2007/2008 and 2001/2002.

In other words companies are currently much more vulnerable to a decline in incomes and/or rise in interest rates that in the previous two cycles.

… At face value, from a net-debt-to-EBITDA ratio point of view, more than half of BBB companies in the US and Europe look more like high yield than high grade.”

– J.P. Morgan Global Markets Strategy, Dec 2018

Goldman Sachs research notes that even the highest quality IG corporates have seen credit quality deteriorate;

“One of our long-standing views related to the BBB debate has been that, within the IG ratings spectrum, downgrade risk was more elevated among A-rated issuers, relative to their BBB-rated peers.

This view has continued to play out through 4Q2018: over $176 billion of debt has migrated into BBB territory from the A bucket; … For full-year 2018, $268 billion worth of A-rated bonds have migrated into the BBB bucket; the second highest amount post-crisis …”

– Goldman Sachs Credit Strategy Research, Dec 2018

Assessing credit quality is nuanced and goes beyond just the few metrics listed above.

For example, in a goldilocks environment of decent economic growth, combined with ultra-low interest rates, companies can sustain higher debt and leverage levels. However, when those conditions change, companies get into trouble if they can’t adjust their balance sheets quickly enough.

For this reason, one area worth closer scrutiny is ‘fallen angel’ risk.

In the context of credit markets, a fallen angel refers to a company whose bonds start with a high quality IG credit rating but then transitions to a below IG rating (known as ‘high yield’ or ‘junk’ bonds). Often this happens because the company has taken on too much debt but can also occur due to worsening economic conditions or changes in certain industries.

This can become very disruptive because many of the largest credit funds and ETF’s can only hold IG bonds. So, as bonds drop to a junk rating those funds become forced sellers. If enough angels fall, a disorderly market sell-off can result.

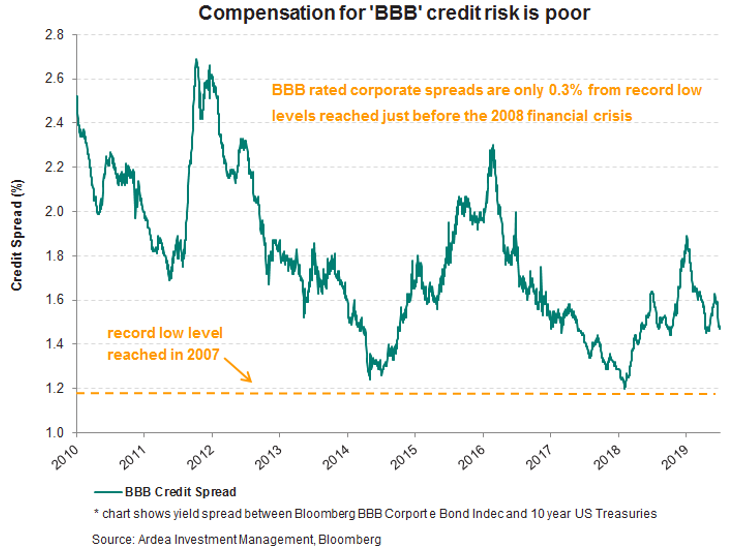

At the same time, the compensation for taking ‘BBB’ credit risk (i.e. companies rated closest to fallen angel status) has dropped to very low levels.

The chart below shows the average additional yield (i.e. ‘credit spread’) offered by USD ‘BBB’ rated corporate bonds compared to US government bonds, which is nearing the record low levels reached just before the big 2008 credit sell-off.

There are mixed views on deteriorating credit quality and fallen angel risk. Perhaps everything will be fine, as the credit bulls argue.

However, getting back to the core principle of risk vs. return, we’re at a point in the cycle where investors are just not getting paid enough to stick around and find out whether or not the downside scenarios play out.

The underappreciated structural risk is liquidity

Liquid investments are those that can be easily sold in sufficient volumes, whenever needed, without incurring punitive transaction costs. Illiquid investments are those that fail to meet these criteria to varying degrees. (Liquidity is a spectrum rather than a binary concept).

The additional return an illiquid asset offers above a comparable investment that’s very similar in all aspects other than liquidity is referred to as the illiquidity risk premium. This is what investors earn explicitly for taking liquidity risk.

Even long-term investors value liquidity in order to maintain flexibility of asset allocation or access to cash and that desire is often highest at times of market stress, when liquidity is most tested. For these reasons, liquidity risk always needs to be accounted for when comparing investments.

While there is always a price for bearing liquidity risk, material liquidity risk may not be appropriate for certain portfolios at any price. For example, defensive portfolios where investors expect to be able to redeem their investment at any time and particularly in adverse market conditions.

On this point, it’s important to appreciate structural changes in fixed income markets since 2008 and the way in which liquidity in some parts of the market has been compromised as a result.

Unfortunately, it’s not always clear during the good times as to how badly liquidity can deteriorate when markets turn.

For example, within the defensive fixed income segment, the common assumption is that investment grade bonds are liquid. While this assumption does still hold for a specific subset of very high quality government bonds, it is no longer true for a growing portion of the corporate bond sector (i.e. bonds issued by companies).

In fact, it’s widely underappreciated just how much corporate bond trading liquidity has deteriorated in the past ten years and how much of this liquidity risk now sits in funds sold to retail investors.

A research paper done for a US market regulator explains it this way;

“While banks have been retreating from the bond market, investors have been charging into it. This is a direct result of central banks’ easy money policies: by driving interest rates to record lows, these policies pushed investors – even income starved mom and pop investors – into riskier assets …

The result: large numbers of investors are crowded into the same trades. That causes prices to trend strongly in one direction, but may leave the market vulnerable to a sudden correction if everyone wants to sell at once.

In theory, investors can exit an open ended mutual fund or an ETF at will. But the growing popularity of these funds forces them to invest in an even larger share of less liquid bonds. If everyone wants to exit at once, prices could fall very far, very fast.

A lucky few may get out in time. Others will probably get trampled.”

– US Securities & Exchange Commission, ‘ The bond liquidity crunch’, March 2016

This topic is explored in more detail here.

Corporate bonds in a broader portfolio context

While corporate bonds offer the potential for higher yields than government bonds, they also come with greater downside risks in adverse environments.

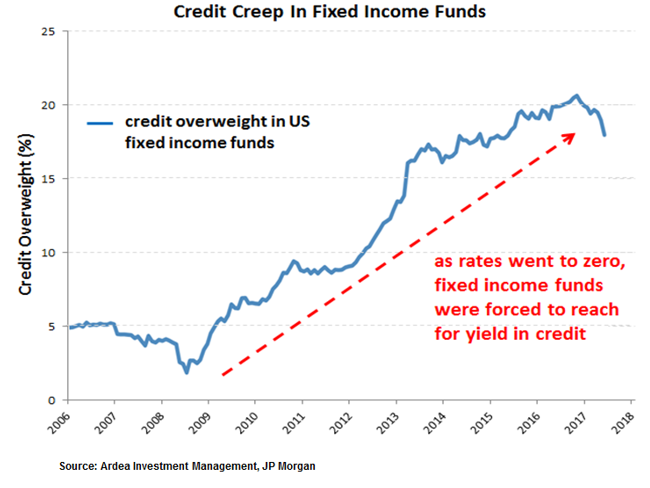

In the post-GFC era, corporate bonds have been a favourite sub-asset class within FI for yield hungry investors. As a result, there has been a pronounced ‘credit creep’ phenomenon whereby even ‘defensive’ FI portfolios have consistently increased allocations to credit investments in search of higher yields.

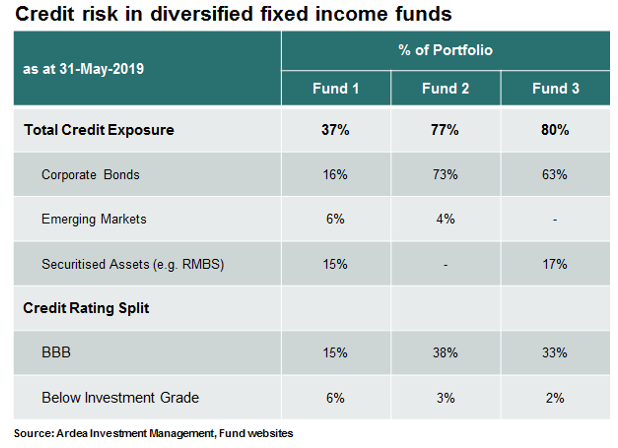

For example, here are the portfolio allocations of some popular ‘defensive’ FI funds;

This ‘credit creep’ has resulted in substantial overweight credit positions across many FI portfolios.

In fact, this persistent credit overweight may have been THE dominant driver of their performance, as this research paper pointed out;

“We find remarkably consistent results across categories: a large portion of active FI manager returns can be explained by exposure to credit markets …

It does not necessarily imply that active FI mangers are buying HY corporate bonds en-masse. But it does suggest whatever it is they are doing (carry trades, overweighting securitized assets that embed credit risk, etc.) ends up providing the investor with something that resembles – and is highly correlated with – HY exposure.

This is hardly comforting for an investment into an asset class that is meant to provide diversification from equity markets”

– AQR, “The Illusion of Active Fixed Income Diversification” 4Q17

It’s therefore not surprising that portfolios overweight corporate bonds generally did well from 2009 to 2017, as credit markets globally experienced one of their biggest bull markets ever over this period.

However, that same credit exposure becomes a loss generating headwind in adverse market environments … right when the ‘defensiveness’ of the investment is needed most, which is exactly what we saw in Q4 2018.

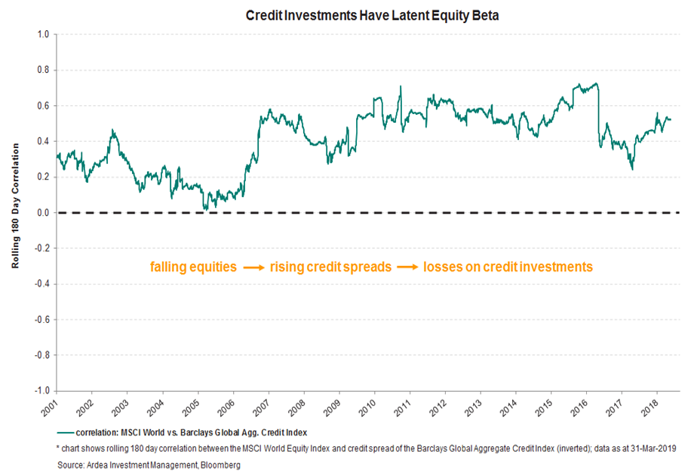

This is because credit investments have ‘latent equity beta’, which means they can behave independently of equities in benign market environments but then become highly correlated to equities on the downside, incurring losses at the same time as equities are falling.

Why is this?

When equity markets decline, credit spreads tend to increase, causing losses on credit investments. This is because of the common causal relationship linking the two – the same factors causing equity markets to decline ( a weakening economic outlook, poor corporate earnings, risk aversion etc.) also tend to impact investor perception of credit risk in the same way.

For example, if economic conditions weaken significantly, the profitability of companies will be hurt, potentially leading to balance sheet stress and elevated default risk. These factors would impact both equity and credit markets negatively.

This is why credit spreads generally increase when equity markets fall, having a negative impact on corporate bond prices. The lower the credit quality of the bond, the more pronounced this effect can be.

This positive correlation between credit and equity returns is show in the chart below;

This relationship is also widely acknowledged across academic literature and practitioner experience;

“The upward trend in the equity-credit correlation is consistent with Warren (2009), who finds that equity betas of investment-grade corporate bond excess returns roughly doubled in the ten years following 1999 compared to the preceding ten-year period.

The positive relationship between equity and corporate bond returns is also consistent with the Merton model and is by now a well-documented observation in the empirical literature (Cornell and Green, 1991; Shane, 1994; Reilly and Wright, 2001; Avramov, Jostova and Philipov, 2007).”

– Norges Bank, ‘Corporate Bonds in a Multi-Asset Portfolio’, Sep 2017

Highly rated investment grade corporate bonds, which are commonly labelled as ‘safe’ or ‘defensive’, exhibit a more subtle version of this correlation.

In benign environments and during modest equity sell-offs, they can exhibit low correlation to equities (i.e. they have minimal equity beta). However, in severe equity sell-offs they get dragged down as well as their equity beta increases. Unfortunately, it’s precisely in these times that investors look to uncorrelated defensive investments to help offset their equity losses. Latent equity beta rears its head at the worst possible times.

This is a case where failing to look beyond labels can actually lead to doubling up rather than diversifying risks.

As the same Norges Bank research report points out, adding corporate bonds to a portfolio that is already exposed to equities actually increases rather than diversifies equity risk;

“The total volatility of all equity-bond portfolios increases as we introduce corporate bonds, as we are essentially increasing the allocation to risk factors already captured by the pure equity-Treasury portfolio.

Of critical importance for the portfolio properties of corporate bonds, we find that corporate bond excess returns have historically been positively correlated to equity excess returns, while moving counter to excess returns on Treasuries.

… The upshot of this is that credit risk acts as a diversifier in a portfolio dominated by interest rate risk, while an allocation to corporate bonds has historically increased the overall volatility of multi-asset portfolios dominated by equity risk.”

These dynamics are particularly relevant in the current environment because the equity beta of credit investments can increase when bond yields are very low, which raises the question of how much (if any) corporate bond exposure is appropriate for the ‘defensive’ allocation within a broader investment portfolio. (see here and here for details)

Corporate bonds, particularly the ‘safe’ investment grade segment, are widely perceived as being defensive investments … but the reality was different last year.

In 2018, as equities experienced large drawdowns, segments of the IG corporate bond markets had their worst year since the 2008 financial crisis, which is not how defensive investments should behave.

This is not a blunt proposition about whether corporate bonds are good or bad, but rather the more subtle consideration around adequate compensation for risk and the roles that investments play in a broader portfolio.

Exposure to credit beta had been a tail wind that many yield seeking FI investments benefitted from for many years, but there are now a growing number of scenarios in which credit exposure actually becomes a return drag.

More importantly, given the defensive role that investors generally expect FI to play as part of their broader investment portfolios, it’s important to look beyond labels by scrutinising what exactly is in a portfolio that claims to be defensive, thinking about how various types of bonds may behave in different scenarios and how they will interact with other investments in the portfolio.

The worst of both worlds are bonds that behave like defensive FI in benign environments but like equity investments on the downside.

Appendix

What is credit risk?

At a high level, bonds can be divided into two buckets – those that carry material credit risk and those that don’t. The former largely comprises bonds issued by high quality governments. The latter is made up of bonds issued by companies (e.g. corporate bonds) and lower quality governments (e.g. emerging markets).

In the same way that companies can borrow money via loans from banks, they can also borrow money from investors by issuing bonds in corporate bond markets.

The interest rate that companies pay on these bonds is typically higher than what a government borrower would pay, which means the yield (or income) an investor earns from investing in corporate bonds is usually higher than what’s available from government bonds.

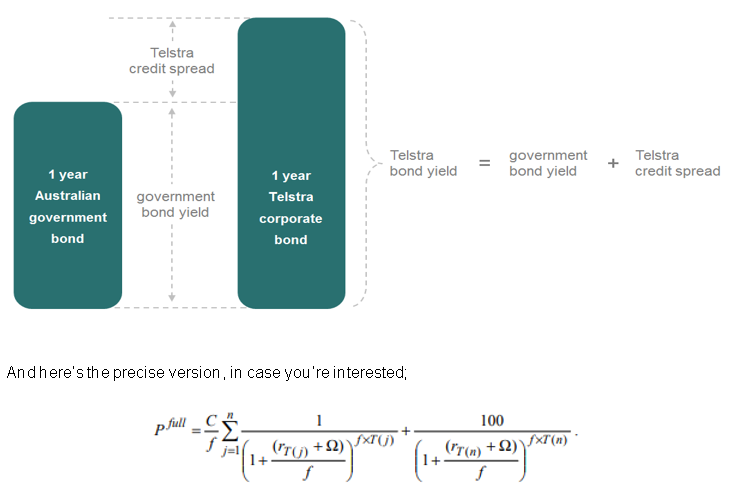

For example, in late 2018 Telstra issued a one year bond, which effectively means they borrowed money from bond investors for 1 year. At the time of writing, that bond offered an extra yield of 0.76% above what was available from investing in a one year Australian government bond.

That additional yield is called a ‘credit spread’. In this case, the term ‘spread’ refers to the difference in yield between a corporate and government bond.

The precise calculation of credit spreads can be complex, but for the purposes of this discussion it’s sufficient to conceptualise them like this;

Credit spreads represent additional compensation (i.e. higher yields) that investors demand in return for taking credit risk. When credit spreads increase, corporate bond prices drop and vice versa.

The first component of credit risk is ‘default risk’, which is the risk that a bond issuer fails to repay investors according to the terms of a bond. Corporates typically (but not always) have higher default risk than governments and therefore investors demand additional compensation to invest in corporate bonds.

However, there is more to credit risk pricing than just default risk alone.

In fact, it is well established in academic literature and market experience that default risk is actually not the major driver of returns for investment grade (IG) corporate bonds in particular. If you considered default risk alone, you would reach the erroneous conclusion that credit spreads represent free money to investors because they consistently over-compensate relative to actual default losses, which are rare.

However, this excess compensation is not free money. Rather, it compensates investors for all the other risks, beyond default risk, that they are exposed to. For IG credit markets in particular, these other risks can actually be more important drivers of credit spreads (and corporate bond returns) than default risk.

They include compensation for uncertainty, risk aversion, equity beta, funding risk, credit rating bias, fallen angel risk, recovery rates, tax effects, interest rate dynamics and liquidity risk 1 .

It’s also important to understand that credit spreads, and therefore corporate bond prices, are dynamic. In the same way that equity valuations re-rate as a company’s prospects change, credit spreads also adjust to reflect changing market perceptions of credit risk.

This means even buy and hold investors in high quality corporate bonds can experience material volatility in their return profiles. For example, as Telstra’s business outlook worsened in 2018, its stock experienced significant volatility, its credit rating was downgraded, its credit spreads increased and bond prices dropped.

When reviewing the performance of credit investments, there can be a misconception that returns only come from the yield / income (i.e. the interest being paid on the bonds). While this is an important source of return, movements in credit spreads can actually be more important return drivers.

In the years following the 2008 financial crisis, corporate bonds (and credit markets more broadly) had the dual tailwind of high yields (so the income component of return was high) and declining credit spreads, which boosted bond prices and delivered capital gains on top of the income.

In 2018 that dynamic completely reversed and turned into a dual headwind. The yields available from corporate bonds were already very low (so the income component of return was low) and increasing credit spreads caused capital losses, resulting in poor returns.

In assessing the outlook for credit returns, it’s important to recognise the role that credit spread movements have played historically and how that might change going forward. In particular, to recognise that the boost they have given to credit returns in the past may actually turn into a significant performance drag in the future.

1 uncertainty – because we can’t predict expected default losses with certainty; risk aversion – corporate bonds have asymmetric return profiles with limited upside vs. disproportionately large downside; equity beta – corporate bonds follow economic cycles just as equities do; funding risk – many market participants are sensitive to their own funding costs when investing in corporate bonds; credit rating bias – already highly rated bonds are more at risk of downgrade than upgrade; fallen angel risk – many investors can only hold bonds with a certain credit rating and can therefore be forced to sell and crystallise a loss on a downgrade; recovery rates – how much you recover from selling the company’s assets in liquidation can vary through economic cycles; tax effects – corporate and government bonds can be taxed differently; interest rate dynamics – correlations between credit spreads and interest rates vary through cycles